Financing for equity in primary and secondary education

1. Education resources to subnational governments

2. Education resources to schools

3. Education resources to students and families

4. Social policies and family support programmes

Introduction

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) began a process of decentralizing its education system through the 2006 reforms, which transferred certain administrative and fiscal responsibilities to the provinces. While this reform formally granted provinces the authority to collect revenues and manage service delivery, in practice, the allocation of education resources has remained heavily shaped by central-level institutions. This tension between constitutional decentralisation and continued central oversight defines today’s financing flows and institutional roles in the education sector.

Classical education in the DRC is structured into preschool, primary, secondary, and higher education. Historically, primary education lasted six years and secondary education was organized into general, technical, and vocational tracks of varying cycle lengths. With the 2016 - 2025 Sector Strategy, however, the government introduced an eight-year cycle of basic education, combining six years of primary with the first two years of lower secondary to guarantee continuity in education before students enter specialised tracks.

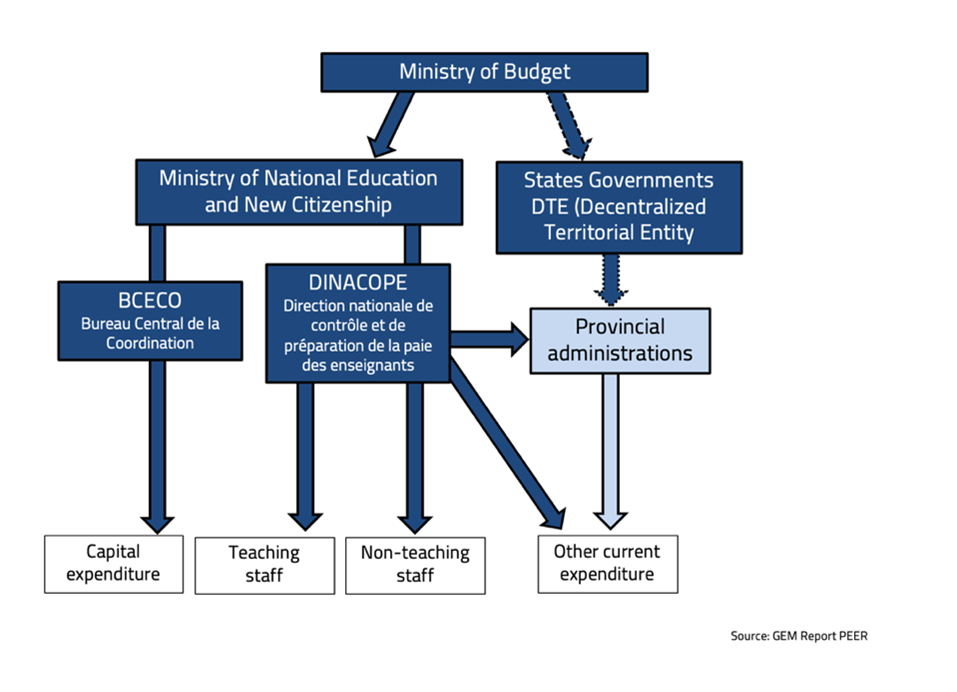

Building on this system structure, the Ministry of National Education and New Citizenship (EDU-NC), formerly known as the Ministry of Primary, Secondary and Technical Education (MEPST), oversees general primary and secondary education, including technical and civic education. EDU-NC administers 60 educational provinces, known as PROVED, across the country’s 26 administrative provinces. Despite the decentralised framework, the Ministry retains central responsibility for managing the salaries of teachers and administrative staff. These functions are carried out through DINACOPE (Direction nationale de contrôle et de préparation de la paie des enseignants), formerly SECOPE, a specialized technical unit under the ministry. In addition, the Ministry oversees capital investments such as school construction and classroom rehabilitation, which are implemented through the Bureau Central de Coordination (BCECO).

Figure 1. Flows of public funding for public educational institutions in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Reference: GEM Report PEER team, based on Public Expenditure Review of the Education Sector in the Democratic Republic of Congo, World Bank (2015)

1. Education resources to subnational governments

In principle, according to Article 175 of the Constitution, the central government allocates 40% of the tax revenues to the provincial governments, who then determine the share of funding to be directed toward provincial education departments This process follows the recommendations of the Priority Action Plan of the government at the national level and the three-year Priority Action Plan at the Provincial level.

The central-level education ministry directly allocates earmarked education budgets to provincial education divisions for specific programmes and operational needs, such as expanding complementary primary education and supporting teacher training. While the September 2023 ITAP evaluation confirms that no equity-oriented allocation formula currently exists in the DRC, the Ministry has indicated plans to prioritise resources for initiatives with high impact or for areas requiring greater support.

2. Education resources to schools

Incentives for Teachers (Incitations pour les enseignants)

Teachers working in underserved areas will receive a hardship allowance equivalent to approximately 25% of their base salary, according to the 2016–2025 Education and Training Sector Strategy. The specific criteria and implementation procedures will be developed through interministerial consultations. In addition, to encourage teachers to settle locally, the construction of teacher housing in these hardship zones will be integrated into the national school infrastructure development programme. By 2025, the strategy aims to give 10% a bonus for working in remote areas.

At the same time, in July 2025, the government announced its draft salary policy a broader revalorisation of teachers’ pay, which includes an increase in the base salary, as part of efforts to improve motivation and retention. However, while the draft is available, its practical implementation remains uncertain.

Encouraging Girls’ Education (Encourager la scolarisation des filles)

According to the 2016–2025 Education and Training Sector Strategy, the DRC government has adopted targeted policies to eliminate gender-based barriers in education and improve girls’ school enrolment. Key measures include prioritising enrolment in the three provinces with the lowest rates of girls’ attendance, distributing school grants in these provinces, and mapping disparities in school infrastructure to guide the construction of new schools and classrooms by 2025. The strategy also highlights the importance of increasing the number of female teachers to serve as role models and support figures, particularly in underserved areas. In line with efforts to address inequality in access to education, according to the activity Report from June 2024 to February 2025, the Ministry plans to award scholarships to 49,047 girls enrolled in 297 public secondary schools in Kasai province. These scholarships cover all school fees, certification and technical examination costs, and provide financial support to families to help retain girls in school.

3. Education resources to students and families

Direct assistance to families (Aides directes aux familles)

The 2016–2025 Education and Training Sector Strategy outlines initiatives to reduce the remaining education costs borne by families, with additional measures led by EDU-NC targeting areas of extreme poverty. These include providing school uniforms and supplies at reduced prices, as well as implementing compensation policies to help families enrol and retain their children in school. This targeted direct assistance is aimed at specific categories of children and families, to support 10% of the country’s students by 2025. However, the strategy does not specify how areas of extreme poverty will be identified, nor does it clarify the mechanisms for targeting beneficiaries to avoid exclusion.

4. Social policies and family support programmes

Education for Indigenous Students (Scolarisation des enfants autochtones)

Based on the 2016–2025 Education and Training Sector Strategy, the government plans to improve schooling for indigenous peoples, such as the Twas, and riverbank settlements through integrated pilot programmes that address broader living conditions, including food, health, and livelihoods. These education initiatives will be part of larger multi-sectoral efforts and will be implemented by experienced community-based or non-governmental organizations rather than education authorities. By 2025, the programme aims to provide subsidies to 300,000 students.

Evidence of implementation can be seen in partnerships with community-based organisations such as Humana People to People Congo, which, in collaboration with the Ministry of Education. One of the initiatives place a specific focus on indigenous students. For example, in Boyabu, peace education projects brought together Central African refugee children and local indigenous communities, organising them into school peace clubs and enrolling 100 refugee children in school in 2024. While these examples demonstrate progress, the scale of reach remains modest compared to the government’s target of 300,000 students.

5. School meal programmes

As of 2025, the DRC does not have a national school meal programme, but WFP has operated school feeding for over 20 years in provinces such as Kasai Central, Tanganyika, South Kivu, and North Kivu, serving up to 500,000 students annually with daily nutritious meals of cereals, pulses, oil, and salt. The programme supports enrolment, retention, and nutrition while stimulating local economies through home-grown sourcing from smallholder farmers, particularly women. The government actively supports these efforts through policy commitments, including a US$10 million budget line under the 2019 free primary education initiative, alignment with national education and social protection strategies, and membership in the School Meals Coalition to scale up towards SDGs. Meals follow nutrition guidelines and are complemented by fresh local produce, deworming, and WASH activities, addressing stunting and improving learning amid high food insecurity.

However, the 2016–2025 Education and Training Sector Strategy includes measures to establish school cafeterias in nearly 3,000 primary schools by 2025. This initiative aims to promote equitable access to education by supporting disadvantaged and marginalised populations, especially those in rural and vulnerable communities. A national roadmap for implementing a school feeding strategy has also been approved, with plans to scale up school meals nationwide. This effort is expected to significantly reduce dropout rates, particularly in the most vulnerable areas.

This profile was reviewed by Isidore Murhi Mihigo, Researcher at the Université Catholique de Bukavu.