Climate change communication and education

2. Climate change education and training in the country

3. Climate change communication in the country

i. Climate change context

The Republic of Fiji is an island nation of the Melanesia region in the South Pacific. Fiji consists of 332 islands (around 110 are inhabited), and the territory also includes many smaller islets. According to the Bureau of Statistics, Fiji had a population of 893,468 people in 2021. Two main islands—Viti Levu and Vanua Levu—account for 87% of Fiji’s landmass and 96% of its population.

According to the Global Carbon Atlas, Fiji’s per capita carbon emission in 2021 was 1.6 tCO2/person, ranking it #146 out of 221 countries being monitored. Their 3rd National Communication (2020) reported that most of the carbon dioxide (CO2) produced by the nation came from the energy sectors, and smaller amounts of methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) came from the agriculture sector.

In 1993, Fiji ratified the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) as a Non-Annex I Party. Fiji ratified the Kyoto Protocol in 1998 and accepted the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol in 2017. Fiji also ratified the Paris Agreement in 2016.

Fiji is facing severe threats related to climate change, including tropical cyclones, rising sea levels, floods, and landslides, as documented in the Climate Risk Country Profile: Fiji (2021) that was produced by the World Bank Group. As one of the most vulnerable nations to climate change, Fiji’s most pressing climate challenge is effectively adapting to intensified climate impacts.

Fiji declared a climate emergency and committed to Net Zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 through the National Climate Change Act in 2021.

ii. Relevant government agencies

Climate change

The National Climate Change Policy (2012) advocated for the establishment of a separate ‘Climate Change Unit,’ which was later assembled as the Climate Change and International Cooperation Division (CCICD) within the Ministry. The CCICD is currently under the Office of the Prime Minister and is responsible for launching and implementing Fiji’s national policies and strategies related to climate change.

The Division is directly responsible for addressing climate change policy-related issues, and it works with various stakeholders, including government agencies, non-governmental organizations, regional and international agencies, and development partners. The Division is the agency responsible for preparing and submitting Fiji’s national reporting related to international agreements, and also acts as the Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE) focal point for Fiji.

With waterways being in a unique position for Fiji’s economic development, the Ministry of Waterways and Environment concentrates on mitigating the effects of climate change on waterways and coastal areas. This includes flood mitigation, agricultural production and productivity, and mitigation of climate change effects. The Ministry identifies the challenges and opportunities for creating environmentally sound climate-resilient strategies by addressing the waterways risks and mitigation measures.

The Ministry of Health and Medical Services focuses on building human health resilience to deal with climate change impacts.

Education and communication

The Ministry of Education, Heritage, and Arts is the main agency for education at the national level. The Ministry oversees primary and secondary education, as well as technical and employment skills training, and it is responsible for producing national education policies and incorporating climate change–related content into the curricula.

The Ministry works with other government ministries such as the Ministry of Employment Productivity & Industrial Relations to incorporate green skills into vocational training and employment opportunities.

Fiji Higher Education Commission is the autonomous governance body that governs higher education; the head of this Commission is appointed by the Ministry of Education, Heritage, and Arts. The Commission ensures that climate change is included in higher education programmes.

iii. Relevant laws, policies, and plans

Climate change

The Ministry of Strategic Planning National Development and Statistics introduced the Green Growth Framework (2014) to more rapidly achieve Fiji’s three pillars of sustainable development toward managing the escalating effects of climate change and building resilience to climate change and disasters.

The National Development Plan (2017)—comprising a 5-year and a 20-year plan—was developed by the Fijian Government. The National Development plan mentioned climate change throughout; in education particularly, the Plan anticipated incorporating the topic of climate change into the curriculum, hoping it “will enrich students’ understanding of wider social issues” (p. 35). The Plan further suggested including climate change in training and awareness in youth empowerment programs, water conservation, and farmers’ approach to climate-related agricultural issues.

The Government of Fiji drew out the Nationally Determined Contribution Implementation Roadmap 2017–2030 in 2017, providing guidance to mitigation actions and climate finance allocations. The Roadmap mentions the elements of Action for Climate Empowerment and includes education and public awareness throughout the mitigation actions, which would also contribute to Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), including SDG 4 (Quality Education) and 13 (Climate Action).

The National Adaptation Plan (NAP, 2018) contains 160 action-oriented adaptation measures, which were to be prioritized over five years. The NAP includes content and adaptation measures for climate change education and training, aligning with the time frame of the National Development Plan (2017). These adaptation measures consisted of ten systems components, including climate change awareness and knowledge. Notably, it stressed the importance of integrating traditional and scientific knowledge into the curricula.

The National Adaptation Plan also dedicated one section to ‘climate change awareness and knowledge,’ suggesting that this is an efficient vehicle to address the Nation’s challenges regarding information, knowledge, and technology adaptation barriers.

The implementation of the National Adaptation Plan provides details regarding climate justice. For instance, climate change awareness and knowledge needs to be inclusive of all stakeholders and communicated in appropriate languages, especially for low-income and disadvantaged populations. Communications also need to incorporate Indigenous knowledge and involve faith-based organizations. Developing relevant materials and educational methods is also crucial to achieving climate justice because it recognizes audience segmentation and that various social groups experience multiple issues brought on by climate impacts.

Fiji’s Low Emission Development Strategy 2018–2050 (2018) emphasized the importance of education, training, and awareness across the business sectors. The government recognized the essential role of education in preparing the future workforce to be climate-ready and transition to a low-carbon society, as stated below:

Fiji’s own system must deliver the tools required for an intergenerational response to climate change. It will take considerable time to develop and establish the curricula and train the educators, and even longer to benefit the workforce. Therefore, it is crucial to start immediately on actions to transition the education sector to better support low carbon growth. (p. 205)

However, because it is only meant for strategic planning, the Strategy only provided an overview and guidance for bringing climate change communication and education into the mainstream in Fiji. The actual planning and incorporation of climate change into education will rely on government and non-government actors in each business sector. The Strategy also incorporated a justice lens in its planning for climate change–related educational programs. Equal access to climate change communication and education for the Indigenous community, women, and youth was considered in the Strategy.

The National Climate Change Policy (2018) was developed to reflect the most recent priorities and framework outlined in Fiji’s National Development Plan (2017). The Policy included content for several Action for Climate Empowerment elements. For example, the Policy’s objective 5 outlined that climate change should be integrated into the national curriculum, responding to “new employer competency requirements and desired skill sets further supporting the development of a climate-ready workforce” (p. 72).

The Policy also outlined the importance of training and capacity building, public awareness, and public access to information in the just transition to Net Zero. At the policy level, the National Climate Change Policy indicated that the Climate Change and International Cooperation Division should undertake reporting on Sustainable Development Goals and establishing climate change communication strategies.

Fiji’s Parliament passed the National Climate Change Act in 2021, providing a legal framework for the country’s climate change responses. The Act demanded the integration of climate change into all levels of the curricula from K–12 education to higher education, and specifically required that training in the Ministry of Economy should address climate mitigation and adaptation and the economic implications of climate change. Additionally, the Act provided a directive to improve public awareness of climate change, such as educational campaigns on sustainable ocean management.

The Act also stressed the importance of developing a national climate change communications strategy, as stated below:

…a national climate change communications strategy to guide the dissemination of climate change-related information through various formats, media types, languages, and other communication channels to increase the consistency of State entities’ communications on climate change and improve public awareness, risk-reduction, and preparedness. (p. 38)

The Act incorporated a climate justice lens, an Indigenous perspective, and a nature-based approach into its provisions, and also included minorities such as disabled people, women, youth, and Indigenous peoples in the development and implementation of the policy.

As planned in the Updated Nationally Determined Contribution (2020), the Fijian government is committed to reducing vulnerability and increasing the nation’s climate resilience by developing communication plans that improve awareness about climate mitigation and adaptation. Climate justice was strongly emphasized in the updated Nationally Determined Contribution to ensure “equity, justice, inclusion, transparency, and accountability in all climate actions” (p. 18).

The Fiji National Climate Finance Strategy (2022) was developed by the government in 2022 with technical support from the World Resources Institute and financial support from the German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation, and Nuclear Safety. The Strategy outlined training and awareness programs in water, waste, and agriculture as means to empower communities to manage their climate risks. The Strategy also explicitly prioritized climate change education within the Ministry of Forestry, focusing on developing training programs to elevate the capacity of the Ministry to better manage Fiji’s forests.

Education and communication

The Kindergarten Curriculum Guidelines for the Fiji Islands (2009) recognized the value of the natural environment to young children. The Guidelines outlined many ways to incorporate exploring and investigating nature into the kindergarten curriculum. However, it did not explicitly include climate change as part of early childhood learning.

The National Curriculum Framework (2013) recognized the necessity of educating students and preparing them for climate adaptation and mitigation through the inclusion of a ‘climate change education’ theme under the ‘Education for Sustainable Development’ in its curriculum perspectives. The Framework addressed, “the inclusion of climate change in the curriculum will stimulate children and students to demand, generate, interpret and apply information on current and future climate challenges” (p. 28). The Framework also stated that Indigenous and cultural approaches were as crucial as scientific approaches for climate adaptation and mitigation.

Fiji’s Education Sector Strategic Development Plan (2015) focused on strengthening students’ capacity for sustainable development under the umbrella of ‘quality education.’ There was no mention of climate change in the Plan.

iv. Terminology used for Climate Change Education and Communication

In Fiji, climate change communication and education were mainly tied to Education for Sustainable Development in education-related documents. The National Curriculum Framework (2013) introduced the theme ‘climate change education’ under the ‘education for sustainable development’ section. The Framework defined ‘climate change education’ as, “children and students will learn to value local Indigenous and cultural knowledge about their immediate environments and at the same time will learn about global and scientific approaches to climate change mitigation and adaptation” (p. 28).

The term ‘climate change awareness and knowledge’ was used in the National Adaptation Plan (2018), the Monitoring and Evaluation Framework for National Adaptation Plan Process (2020), and the Climate Change Act (2021). The 3rd National Communication (2020) used the term ‘climate change education and awareness.’

The National Adaptation Plan (2018) ‘climate change awareness and knowledge’ section mainly focused on climate disaster and risk management adaptation, as well as addressing climate change using both traditional and scientific knowledge. In the Monitoring and Evaluation Framework for National Adaptation Plan Process (2020), ‘climate change awareness and knowledge’ was described as “enhancing understanding by increasing the flow of relevant information to relevant adaptation stakeholders” (p. 5).

The Climate Change Act (2021) also used the term ‘climate change communication,’ referring to the “dissemination of climate change information through a variety of formats, media types, languages and other communications channels to increase the consistency of State entities’ communications on climate change and improving public awareness, risk-reduction, and preparedness” (p. 38).

v. Budget for climate change education and communication

The Climate Change and International Cooperation Division, under the Office of the Prime Minister, oversees the flow of all climate funding and is responsible for domestic climate finance resources.

The National Climate Change Policy (2019) indicates that there is a budget for all climate finance proposals related to domestic climate change–related capacity building.

The Ministry of Education, Heritage, and Arts was allocated US$ 489.9 million in the Budget Estimates 2022-2023 (2022). Of these funds, only US$ 5,000 was planned to be used for climate change and environmental awareness. There was a budget for capacity building and communication in the plans of almost every Ministry, but none were specifically for addressing climate change.

The regional program Coping with Climate Change in the Pacific Island Region (CCCPIR), funded with US$ 20.6 million by the German government, included a focus on climate change education. The program operated between 2009 and 2015.

In 2012, Fiji signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the German Society for International Cooperation and received funding to incorporate a climate change syllabus into the primary, secondary, and tertiary curricula. The exact amount of this funding was not available at the time of this review. Nevertheless, the 3rd National Communication (2020) reported that in 2012, the Ministry of Education took the lead in integrating climate change at all levels of education, including in school curricula.

The European Union Pacific Technical and Vocational Education and Training on Sustainable Energy and Climate Change Adaptation project was being implemented by the Pacific Community in partnership with the University of the South Pacific. The Project’s main objective was to provide regional training and capacity building in the area of sustainable energy and climate change. The Project was funded by the European Union with overall funding of US$ 6.67 million (EUR 6.3 million) from 2014 through 2020.

The Global Environmental Facility funded six climate change–related projects in Fiji worth US$ 14 million. Some of these projects, such as the Support for Regional Oceans, included an element of training.

During 2017–2018, the Canadian government funded a US$ 1 million project through the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) to support the Fijian government’s preparation for the UNFCCC COP23. This Project delivered negotiation training for 12 members of the Fiji National Climate Change Negotiation Team on topics such as adaptation, mitigation, and finance.

The Green Climate Fund was established to provide a climate fund to support developing countries to raise and realize their Nationally Determined Contribution ambitions. According to the National Climate Financial Strategy (2022), the Ministry of Economy proposed climate adaptation and mitigation projects for the Fund. The projects with elements of training and public awareness were worth US$ 73.14 million.

The National Climate Financial Strategy (2022) also included a summary of the climate budget in different economic sectors. The agricultural sector included a budget of US $900,000 for raising awareness.

According to the Country’s 3rd National Communication (2020) under the UNFCCC, the total fiscal spending on climate change and resilience was US$ 178 million in 2018–2019, accounting for 11% of the national budget in that year. The document did not make it clear how much of these funds were used for climate change–related education and communication.

The Fijian Government and the Forest Carbon Partnership Network (World Bank) signed a US$ 12.5-million Emission Reductions Payment Agreement in 2021. The Agreement rewarded efforts to reduce carbon emissions from deforestation and forest degradation through Fiji’s Carbon Fund Emission Reduction Program. The Ministry of Economy and the Ministry of Forestry led the Program, which included training to establish community plantations and woodlots.

The Ministry of Education, Heritage, and Arts called for International financial support for education transformation at the 2022 UNESCO meeting in Paris. Fiji’s UN representative discussed financing climate change action in education at the Transforming Education Summit in New York in 2022.

i. Climate change in pre-primary, primary, and secondary education

Based on the Education Sector Development Plan (2019), as of 2019, there were 737 primary schools, 173 secondary schools, approximately 900 early childhood care and education centers, and 17 specialized schools in Fiji. The Government owns 13 schools, and communities and faith-based organizations acknowledge the rest, with staff and operational funding provided by the Government.

According to the 3rd National Communication (2020), elements of climate change were addressed in the current education curriculum in Basic Science (years 9 and 10) in primary education and in Biology (years 12 and 13), Physics (years 12 and 13), and Geography (year 12 and 13) in secondary education.

The Ministry of Education, Heritage, and Arts revised the National Curriculum Framework in 2013 to incorporate climate change into the relevant content and learning outcomes for primary and secondary school. A theme of ‘climate change education’ was introduced under the curriculum perspective of ‘Education for Sustainable Development.’ However, climate change education was not reflected in the detailed subject matter for primary and secondary education in the Framework.

Learning About Climate Change the Pacific Way (2013) details the inclusion of climate change in years 7 and 8. For example, the Social Science syllabus includes learning about personal and social groups and progresses to “find out the main groups of people in the Pacific and discuss their origins, characteristics and ways of life (including how these can cope with effects of climate change)” (p. 4). In the Basic Science syllabus, climate change content was included in the topics of biodiversity and sustainability, the Earth, and the influence of human activities on Earth such as climate change. The Geography syllabus addresses how different climate types affect human activities and the causes and effects of climate change. However, all syllabus information was found in the Learning About Climate Change the Pacific Way document, and none of these syllabi were publicly available online.

The National Adaptation Plan (2018) mentions a climate change education plan in formal education that is focused on risk reduction and oriented on local action, as stated below:

Regularly update and support the delivery of primary, secondary, tertiary, and vocational education curricula that allow and encourage students to participate in research and risk reduction activities in their local area. (p. 55)

ii. Climate change in teacher training and teaching resources

The UNESCO initiated the SPARCK project in Fiji in 2013, aiming to understand how teachers in Fiji can be better prepared to integrate climate change into curriculum learning. As the Ministry of Education, Heritage, and Arts reported in its Annual Report (2013), a total of 15 senior science teachers from the greater Suva area attended the SPARCK project’s training workshop in Suva. In cooperation with the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme, the Pacific Community, and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, the project developed a picture-based outreach toolkit on climate change and trained teachers and lecturers how to use it.

Through the climate change educational component of the regional program Coping with Climate Change in the Pacific Island Region (CCCPIR), the children's storybook ‘Pou and Miri: Learn about climate change and growing food crops’ was published in 2011 and recognized as an efficient resource for teaching climate change. The storybook was distributed to all Fijian primary schools through the Ministry of Education, Heritage, and Arts including 10,000 copies in English and 5,000 copies in Vosa Vaka Viti.

The Coping with Climate Change in the Pacific Island Region program also developed a teaching resource iTaukei glossary of climate change terms in 2012 called Vosaqali ni Draki Veisau, and they handed it over to the Ministry of Education, Heritage, and Arts.

In 2013, the Red Cross and the Australian Government’s Pacific-Australia Climate Change Science and Adaptation Planning Program developed a series of teaching resources for educators in 15 Pacific Island nations, including Fiji. These climate change education resources included an animated video called The Pacific Adventures of the Climate Crab and a climate crab toolkit.

Learning About Climate Change The Pacific Way: A guide for Pacific Teachers Fiji was launched by the CCCPIR program in 2014. This Guide was developed to help teachers deliver key messages on climate science and climate change effects, mitigation, and adaptation in the classrooms. Following the launch of the Guide, a three-day training of trainers’ program on using the resources in the classroom was organized.

In 2016, the Ministry of Education, Heritage, and Arts and UNESCO launched a book titled Resource Book on Disaster Risk Management that includes traditional knowledge. This book was trialed in 140 primary schools before being adopted, and continuous training on using the book is provided to teachers.

In 2016, UNESCO also developed a teacher training resource titled Climate Change Education for Asia Pacific Small Island Developing States, in partnership with the Malaysian government and university. This training resource strengthened the teachers’ capacity to teach climate change and sustainable development in Asia Pacific small island countries, including Fiji, and targeted both pre-service and in-service teachers at primary and secondary schools.

In 2018, the Ministry of Education, Heritage, and Arts, in collaboration with the European Union Pacific Technical and Vocational Education and Training on Sustainable Energy and Climate Change Adaptation Project and Coping with Climate Change in the Pacific Island Region program, conducted a series of workshops on climate change education for 342 secondary school teachers.

During the 2018 Early Childhood Education national conference, the Ministry of Education, Heritage, and Arts addressed the goal of incorporating climate change education into early childhood education. More than 300 teachers attended the conference.

According to the 3rd National Communication (2020), the Ministry of Economy trained 596 primary school teachers in the Climate Change Education Trainer portion of the trainer’s program, in partnership with the regional program Coping with Climate Change in the Pacific Island Region. The year that this training took place was not available online at the time of this review.

iii. Climate change in higher education

As of 2015, according to the Education Sector Strategic Development Plan (2015), there were 68 recognized institutions in Fiji, of which 23 were registered, 5 were provisionally registered, and 29 had applications under process by the Commission.

The National Climate Change Policy (2018) emphasized that integrating climate change into national university programs—such as courses, degrees, and modules—was critical for building a climate-ready workforce for future generations. Fiji’s Low Emission Development Strategy 2018–2050 (2018) viewed higher education as a training ground for training skilled Fijians. The Strategy specified the incorporation of sustainable transport into the university curricula. The Fiji Higher Education Commission elaborated on the necessity of incorporating traditional knowledge and climate change to prepare the future workforce to tackle climate change.

All three universities in Fiji have developed climate change–related programs. The Fiji National University offers a Postgraduate Diploma Program in Climate Change, Resilience, and Mitigation and a Master in Climate Change, Resilience, and Mitigation; these degrees equip students with scientific knowledge of climate change and analytical skills in climate change–related research, and will prepare future talents in policy-making related to climate change adaptation and mitigation.

The Fiji National University and Monash University have also established a formal climate change partnership. The Monash-FNU Pacific Island Countries Climate Change Research Centre (CCRC) was established in 2022, focusing on policy research in climate change mitigation and adaptation. In 2023, the Pacific Action for Climate Transitions (PACT) Research Centre was established and based across two universities; it focuses on researching the critical links between businesses and climate change and finding solutions for communities.

The University of Fiji set up the Centre for Climate Change, Energy, Environment and Sustainable Development to strengthen and harness research capacity for policy-making, planning, and sustainable development in areas of climate change, energy, environment, science, and technology. The Centre was the driving force in the development of the Master’s Program in Renewable Energy Management. Additionally, the University also offers a Postgraduate Diploma in Energy and Environment. Although neither program is specific to climate change, they are developed in the intersection of energy and environment and offer compulsory courses on climate change.

The University of South Pacific established the Pacific Centre for Environment and Sustainable Development (PaCE-SD) as part of the University’s 1999 Strategic Plan. The Centre conducts research on the environment and offers various degrees and diploma programs related to climate change, including a Postgraduate Diploma in Climate Change that focuses on science, adaptation and mitigation, or disaster and resilience; a Master of Science in Climate Change based on a research thesis; and a PhD in Climate Change also based on a research thesis.

iv. Climate change in training and adult learning

There is a robust Technical and Vocational Education and Training sector with government and private providers.

The seven Key Learning Areas in the National Curriculum Framework (2013) included one area of ‘technology and employment skills training,’ aiming to provide knowledge and skills to students for their future employment.

The National Employment Policy (2018) identified the potential to create ‘green jobs’ in the sectors of construction, sustainable agriculture and fisheries, eco-tourism, and renewable energy sources; these jobs are based on the new training and skills in materials, technologies, and working methods needed in the context of escalated climate change. These priorities identified in the Policy guided the career training program.

Several of Fiji’s national strategic plans, such as the National Climate Change Policy (2018) and the National Adaptation Plan (2018), have included planning on climate change–related capacity building for its future workforce.

The National Adaptation Plan (2018) included building capacity in more segmented target audiences through technical education and/or vocational training. For example, adaptation measure 10.3 focused on government officials, community members, and civil society; 10.4 focused on engineers and other professionals working in the infrastructure and construction trades; and 10.5 focused on private sectors. Such training will improve the capacity of participants to reduce climate-related impacts in their respective fields. Non-formal education and training materials were also addressed by the Plan, with specific demands “to incorporate climate change and disaster risk information where appropriate in a way that encourages and supports individuals to undertake risk-education activities” (p. 56).

Fiji’s Low Emission Development Strategy (2018) has put training for the future workforce at the center of its strategy to transition to a low-carbon society. Across the business sectors, the Strategy guided the development of various vocational training programs for the future workforce, as stated:

The government will strengthen and improve the quality of the technical and vocational education and training (TVET) system relevant to the LEDS sectors by developing a curriculum aligned with the needs of a low-carbon economy labor market. (p. 205)

The Asia Foundation is an international non-profit organization that improves lives in Asia and Pacific nations. From 1995 to 2014, the Foundation’s Pacific Program conducted regional climate-related risk management training for over 7,000 participants from 14 Pacific Island nations, including representatives from Fiji.

In 2012, in partnership with UN Women, the High Commission of India and Barefoot College in Rajasthan India provided six months of training to 10 grandmothers in rural villages in Fiji so they could become ‘women solar engineers.’ The training addressed climate change and helped build local capacity and improve access to clean solar energy. Following the training, the Indian government helped establish the Barefoot College Program in Fiji.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations launched a project called Pro-Resilient Fiji – Strengthening Climate Resilience of Communities for Food and Nutrition Security in 2012, focusing on building climate resilience in agriculture in Fiji. This Project benefited over 30,000 farmers and provided various training, including training for 103 farmers (of whom 60% were women and youth representatives) on community-based disaster risk reduction, and training of trainers for 327 farmers on practical climate-smart agriculture techniques.

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) supported the Climate Change and Food Security Project in Fiji through the Pacific Community. The Project included training and capacity building for communities in relation to adaptation responses in agriculture.

The European Union–funded project, the European Union Pacific Technical and Vocational Educational and Training in Sustainable Energy and Climate Change Adaptation project developed certificate-level qualifications in the fields of climate change resilience and sustainable energy in partnership with the Fiji Higher Education Commission. Since 2014, the Project has worked with the University of South Pacific and offered regionally accredited certificate programs in Fiji, including the Certificate III program Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction and Certificate IV program Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Management through the School of Pacific Technical and Further Education. The Project also supported the Ministry of Youth to deliver the Certificate I program to several rural and remote communities, focusing on the causes and impacts of climate change and adaptation using traditional knowledge.

The National Climate Finance Strategy (2022) prioritized financial investment in 12 climate-vulnerable sectors. The development objectives of numerous sectors placed a strong emphasis on training and capacity building. For instance, training programs on climate adaptation in the agriculture, forestry, and water sectors; career-related training in the transportation sector; and training regarding access to and communication about meteorological data in the disaster risk management sector.

i. Climate change and public awareness

The Fijian government included climate change public awareness in several policy documents. Many awareness campaigns were delivered through collaboration between government agencies and non-governmental organizations.

Fiji’s Low Emission Development Strategy (2018) recognized that increasing awareness of energy efficiency would support the transition to a low-carbon society. These programs, for example, would “increase awareness about the existence and benefits of energy-efficient building design, appliances, and savings” (p. 203).

In the strategies outlined in the National Climate Change Policy (2018), increasing public awareness, specifically on the connection between climate impacts and disaster risks, contributed to the integration of climate adaptation and disaster management priorities.

The National Adaptation Plan (2018) also stressed the importance of increasing climate change awareness and knowledge among stakeholders to strengthen their understanding of climate change and disaster risk and improve their engagement in conversations regarding climate change.

The National Climate Finance Strategy (2022) addressed public awareness of climate change actions in the implementation priorities of agriculture, forestry, gender and social inclusion, and water and sanitation sectors. For example:

Foster awareness and social responsibility about how sustainable forest management intersects with climate change mitigation and adaptation, gender equality, and other social equality issues. (p. 50)

Support community involvement in water resource management by raising awareness and strengthening the capacity of community-based organizations, non-governmental organizations, and government departments to disseminate information about climate-resilient water management to communities. (p. 71)

The Coping with Climate Change in the Pacific Island Region program produced many resources to raise public awareness of climate change between 2012 and 2015. Two examples of these resources are a poster about Fiji Climate Change Facts and a brochure on the Impacts of Climate Change on Agriculture.

The Government of Fiji ran an Energy Conservation and Efficiency Program in 2012 to raise public awareness of the importance of using energy efficiently.

The University of Fiji ran an Eco Contest in 2017 to promote awareness of climate change and sustainable energy among high school students. In the same year, the University of Fiji hosted a series of Awareness Sessions on climate change issues in light of the upcoming COP23; they also delivered presentations on COP23 and climate awareness in selected schools and local communities in Fiji’s Western division.

In 2018, the Water Authority of Fiji launched a two-month water conservation campaign to increase the public’s awareness of the importance of saving fresh water.

The Fiji Government launched an annual Natural Disaster Awareness Campaign between October 2020 and April 2021. This Campaign focused on educating and preparing the most affected communities to better prepare for future climate-related disasters.

Mamanuca Environment Society is a non-profit organization focusing on protecting the marine environment of the Mamanuca Islands in Fiji. Many of the Society’s programs aim to raise awareness about sustainability in general and climate change disaster risk management that is specific to staff and guests of the tourism industry.

ii. Climate change and public access to information

Public access to information was considered essential in Fiji’s various national climate-related policies. Because of the nation’s vulnerability to climate impacts, the government has tried to equip its citizens with timely climate information and critical adaptation knowledge.

The National Climate Change Policy (2018) stressed that enabling the government’s climate change communication capacity was essential to prepare Fijian citizens for climate mitigation and adaptation. The Policy took an evidence-based decision-making approach, and supported public access to information through various formats of dissemination and by constructing data storage and technologies.

To secure the communication on climate change information, the Plan specified support for both private and public media organizations, making sure “the dissemination of climate change, disaster risks, hazard, and disaster information and stimulating a culture of prevention and strong community involvement in sustained public education campaigns and public consultations at all levels of society” (p. 56).

The National Adaptation Plan (2018) focused on developing communication infrastructure, such as building a national platform to link to the Pacific Climate Change Portal, which provides an opportunity for stakeholders to exchange best practices regarding climate adaptation measures and lessons learned, coordinate resources, and discuss research and knowledge gaps.

The government invested in the Fiji Climate Change Portal to ensure data and information were available in a timely fashion, which also fed into the Pacific Climate Change Portal to provide country-specific information and material.

Since 2022, the Pacific Community has hosted a web-based information platform named The Pacific Resilience Nexus for all Pacific climate disaster and resilience knowledge resources, including information critical to Fiji.

According to the 3rd National Communication, the Fijian Government also launched a 4-year program called Digital Government Transformation to build the infrastructure and ensure access to government services and data.

iii. Climate change and public participation

Public consultation was essential in the formation of many critical national climate change–related policies, mostly in the form of multi-stakeholder consultation at national and regional levels.

The development of the National Climate Change Policy (2018) went through public consultation for two years (2017–2019). These included a national consultation, consultations with the Northern Division and Western Division, and consultations with a sample of rural communities.

The Ministry of Economy developed the Low Emissions Development Strategy (2018) with intensive discussions and consultations with a wide range of national, regional, and international stakeholders, including the government, the private sector, academic institutions, development partners, and civil society.

The National Adaptation Plan (2018) advocated for public consultation at all levels of society in climate change communication and education-related events. The Plan addressed stakeholder engagement at monitoring and evaluation exercises at national and sub-national levels. When producing the Plan, the Ministry of Economy organized consultation workshops with stakeholders from experts, the private sector, regional development partners, and national civil society.

The Plan also suggested establishing a climate change communication strategy; the participation from stakeholders at all levels and across all social groups was considered an essential component of the strategy.

There was no mention of public participation in Fiji’s Updated Nationally Determined Contribution (2020). However, the Ministry of Economy went through a 5-month inclusive stakeholder engagement to develop the Nationally Determined Contribution Implementation Roadmap 2017-2030 (2017).

The creation of the Monitoring and Evaluation Framework for Fiji’s National Adaptation Plan Process (2020) went through a 5-month series of consultations with relevant government agencies, including 30 stakeholders from 20 government agencies.

i. Country monitoring

The Education Sector Strategic Development Plan (2015) included content on monitoring and evaluating Education for Sustainable Development programs in the curricula. However, it was not specific to climate change education and there were no detailed indicators.

The Nationally Determined Contribution Implementation Roadmap 2017–2030 (2017) mentioned a Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification System that was used for tracking the progress of the Roadmap, including the assessment of the impact of Sustainable Development Goals and the implementation of capacity building.

The Roadmap also anticipated that a strengthened National Reporting and Inventories System was needed to address new indicators—such as one tracking the impact on Sustainable Development Goals—to make the Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification System more robust. The Roadmap suggested conducting an assessment of the inclusion of environmental education in the school curricula, as stated:

Carry out a baseline study and need assessment in schools and tertiary institutions to evaluate the extent to which Environmental Education is incorporated in the curriculum, identify gaps, and make recommendations for additional elements required; followed by developing content and material to be included in the school curriculum. (p. 27)

According to the National Adaptation Plan (2018), Fiji planned to establish monitoring and evaluation systems in the five-year implementation period of the Plan, including developing a national climate change communication strategy that includes monitoring and evaluation systems.

The National Climate Change Policy (2018) mentioned that the assessment of national resilience included coping capacity, adaptive capacity, and transformative capacity, all of which focused on capacity building for disaster risk management.

The Low Emission Development Strategy (2018) proposed a monitoring and evaluation system to track progress in four different dimensions, including how the policies contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals targets and how they implement capacity building.

The Climate Change and International Cooperation Division of the Ministry of Economy developed the Monitoring and Evaluation Framework for Fiji’s National Adaptation Plan Process (2020). The Framework guided the Division on how to monitor and evaluate the National Adaptation Plan (2018) process, including the components related to climate change communication and education. For example, in monitoring capacity building for disaster risk management, the Framework measured the “number of training programs delivered and number of participants trained” (p. 16). To establish a national climate change communication strategy, the Framework suggested including indicators such as audiences’ knowledge, attitudes, requirements, and “frequency and timing of communications with key audiences” (p. 19) in the monitoring and evaluation system. For monitoring and evaluating climate change awareness and knowledge, the Framework’s measurement focused on stakeholders’ engagement in decision-making and understanding of adaptation. The monitoring system can also be used to determine progress toward the commitments to international policy processes and agreements, such as the Paris Agreement and Sustainable Development Goals.

ii. MECCE Project Monitoring

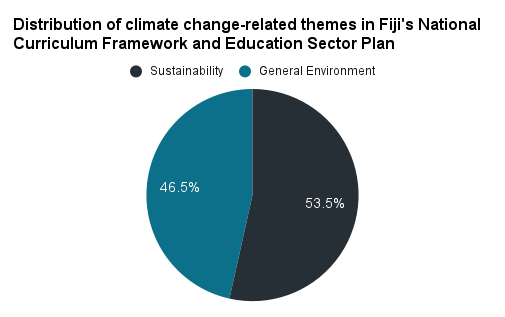

The Monitoring and Evaluating Climate Communication and Education (MECCE) Project examined Fiji’s National Curriculum Framework (2007) for references to climate change, sustainability, biodiversity, and the environment.

Overall, Fiji’s National Curriculum Framework (2007) did not mention ‘climate change’ or ‘biodiversity’; it focused more on ‘sustainability’ and ‘environment,’ with 23 and 20 references, respectively.

The Education Sector Strategic Development Plan (2015) was not analyzed by the MECCE Project.

This section will be updated as the MECCE Project develops.

This profile was reviewed by Dr. Ramendra Prasad, Senior Lecturer, The University of Fiji, and Barbara Biuvakaloloma, Learning & Development Coordinator, Pacific American Fund.