Climate change communication and education

2. Climate change education and training in the country

3. Climate change communication in the country

i. Climate change context

Chile is located in western South America, with a total land area of 2,006,096 km2, and according to the World Bank, it has a population of 19.1 million people (World Bank, 2021). Chile shares borders with Peru to the north, Bolivia to the north-east, and Argentina to the east and south. Chile’s Pacific Ocean coastline is over 8,000 km long, and is characterized by a wide-ranging topography. Approximately 89% of the population inhabits urban areas, concentrated in the centre of the country within the Santiago Metropolitan Area, which is home to 40.1% of the country’s inhabitants (World Bank, 2021).

Chile has four macro-bioclimates: tropical, Mediterranean, temperate and subtropical desert. These climates contain 127 terrestrial ecosystems, with 96 marine ecosystems along the country’s coast. Chile experiences dry southern hemisphere summers (from November to February) and wet winters (from June to August). Approximately 29% of Chile’s land area does not have vegetation, while approximately 39% of its land is grassland and scrub, 26% is forest, and 5% is agricultural land; only around 1% of Chile’s land can be categorized as urban or industrial (World Bank, 2021).

Chile is considered a high-income country and over the last few decades it has become one of Latin America’s fastest-growing economies. Chile is one of three Latin American members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), with a gross domestic product (GDP) of US$$252.94 billion (World Bank, 2021). Despite this economic growth and considerable poverty reduction efforts, more than 30% of the population is recognized as economically vulnerable, and the country’s inequality levels remain high. Efforts in poverty reduction include investments in public health, the raising of the minimum wage, psychosocial support, direct cash transfers, subsidies, and preferential access to social programmes for families living in poverty and extreme poverty.

According to the World Bank, Chile is recognized as vulnerable to climate change impacts, due to a combination of political, geographic and social factors, with key sectors such as fisheries, aquaculture, forestry, agriculture and livestock identified as vulnerable, together with the country’s water resources. Chile is susceptible to the impacts of climate change, in particular mega-droughts, mega-fires and floods.

Specific sectors of Chilean society have been identified as being more vulnerable to climate change. For example, it has been found that women are more vulnerable to climate change than men. Factors explaining this include: the different ways in which men and women spend their time during the day as a result of different gender roles; access to assets and credit; and different treatment from formal institutions. Factors such as these may limit women’s economic opportunities and their ability to participate in policy discussions and decision-making.

Another group that has been identified as being more vulnerable to climate change is communities using traditional agricultural practices (World Bank, 2021).

According to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Chile is a Non-Annex I Party. Chile signed the Kyoto Protocol in 1998, ratified it in 2002, signed the Paris Agreement in in 2016 and ratified it in 2017. According to the United Nations Observatory on Principle 10 in Latin America and the Caribbean, Chile ratified the Escazú Agreement in 2022.

The Global Carbon Atlas calculates Chile’s emissions at 44 tCO2/person in 2021. This places Chile 44th overall in terms of emissions per capita worldwide and categorizes it as a low-emitting country. According to Chile’s Fourth National Communication (2021), the energy sector is the main emitter of CO2 nationally. Emissions can be broken down as follows: 39% energy industries, 33% transportation, 18% manufacturing industries and construction, and 9% other sectors.

In line with the Centre for Justice and International Law, Chile and Colombia have joined forces to request that the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issue an advisory opinion to address the climate emergency. This request was jointly signed by the foreign ministers of Chile and Colombia in 2023, with the hopes of supporting a fair, sustainable and timely response to the climate emergency. The court’s response will guide these countries and others in the region in the development of policies and programmes to uphold their commitment to human rights and environmental treaties, including the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR). The court had not issued its response at the time of writing.

ii. Relevant government agencies

Climate change

Several governmental agencies and organizations are involved in climate change education and communication. The following are the agencies responsible for Chile’s climate change strategy and response:

The Ministry of the Environment is responsible for designing and implementing national environmental policies in the country, as well as coordinating environmental initiatives, promoting sustainable development and consumption, and communicating climate change issues to the broader public. According to the Framework Law on Climate Change (2022) the Long-Term Climate Strategy will be prepared by the Ministry of the Environment with the collaboration of the sectoral ministries. It will be established by supreme decree of the Ministry of the Environment. This government agency also houses Chile’s national ACE focal point.

The Climate Change Office within the Ministry of Environment has been developing a proposal to incorporate climate change into the different levels of both formal and non-formal education. These efforts have resulted in the development of written and audio-visual support material, training, talks and support for the development of teachers and professionals in other subjects on climate change issues.

The Framework Law on Climate Change (2022) has created the Scientific Advisory Committee for Climate Change (Article 19) as an advisory committee to the Ministry of the Environment in relation to the necessary scientific components for the development, design, implementation and updating of the climate change management instruments established in that law.

The Framework Law on Climate Change (through articles 46 and 71) renames the Council of Ministers for Sustainability the Council of Ministers for Sustainability and Climate Change. This council is chaired by the Minister of the Environment and comprises the ministers of agriculture; finance; health; economy, development and tourism; energy; public works; housing and urban planning; transportation and telecommunications; mining; social development and family; education; and science, technology, knowledge and innovation.

The Ministry of Energy is responsible for designing, implementing and communicating energy policies, collaborating with national and international stakeholders, and monitoring progress toward sustainable goals specifically relevant to energy consumption and management.

The Ministry of Economy Development and Tourism is responsible for promoting a new productive development model in the country, effectively responding to the challenges posed by the climate crisis and generating quality employment.

The Ministry of Labour and Social Security oversees and coordinates labour policy in the country, under the pillars of quality employment and inclusion. The ministry’s policies, plans and programmes include directives to address the impacts of the global climate emergency and assist Chile’s shift towards a new productive development model.

Education and communication

The Ministry of Education is tasked with incorporating climate change communication and education into the national curriculum, ensuring that students receive information about environmental sustainability and climate action throughout the different levels of education and training that comprise the Chilean national education system. The Ministry of Education uses several tools and instruments to promote education for respect and protection of the environment, including: reflection days for climate action organized alongside the Universidad Austral de Chile; courses designed exclusively with Educar Chile for teachers to receive information on climate change; and the development of environmental missions within schools together with the Ministry of the Environment and Kyklos.

The Ministry of Science, Technology, Knowledge and Innovation is tasked with funding scientific research related to climate change. The ministry collaborates with the Ministry of Education and other stakeholders to incorporate climate change education in curricula. It does this by disseminating scientific knowledge related to climate change through various channels (such as academic publications, mass media and social media) and working with global organizations and research institutions to publicize knowledge, best practices and research outcomes regarding climate change adaptation and mitigation.

Together with the governmental agencies and academic initiatives involved in national climate change communication and education efforts, a number of Chilean NGOs actively contribute to these efforts on a national level. Among these are the following:

The Terram Foundation focuses on advocacy, policy analysis and public awareness campaigns to communicate the impacts of climate change and encourage sustainable practices.

Fundación Chile aims to promote innovation and sustainability through research, capacity-building, and technology transfer, with a focus on sustainable agriculture, energy efficiency and climate change adaptation. Fundación Chile has developed various initiatives with the Ministry of Education as part of Aprendizaje para el Futuro, to better prepare the Chilean educational system to comply with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 and include environmental challenges as a key element in education.

Fundación Huella Local has a local-level community-centered focus to promote sustainable development and environmental conservation, including initiatives related to sustainable agriculture, renewable energy and waste management.

iii. Relevant laws, policies, and plans

Climate change

The Chilean Constitution (2010) (which in 2023 is undergoing a process of modification through a Constituent Assembly) incorporates provisions on environmental protection. The constitution enshrines Chileans’ right to live in an environment free of pollution and protects the enactment of laws that curtail the exercise of specific rights or liberties to protect the environment.

More recently, the Framework Law on Climate Change (2022) constitutes an effort to confront the challenges posed by climate change and trace a path towards substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions aiming to achieve and maintain emission neutrality by the year 2050. The framework law mandates the creation of national-level management instruments and a ‘long-term climate strategy’. This is to be implemented through technology development and transfer, capacity building within the national government and scientific establishment, and an increase in national funding. The law also mandates the creation of sectoral plans for climate change mitigation for the following sectors: energy, transportation and telecommunications, mining, health, agriculture, public works, and housing. The plans are to include diagnoses, mitigation measures, and monitoring, reporting and verification (MDV) indicators. At the local level, the framework law calls for the establishment of regional climate change action plans and communal climate change action plans, which must include an account of each region’s vulnerability to climate change, mitigation and adaptation measures, and MRV indicators. At the time of writing, no details on the progress of these initiatives were available.

The Framework Law (2022) also outlines new standards regarding greenhouse gas emissions and emission reduction certificates. It also establishes the responsibilities of each national agency, including the Ministry of the Environment, and the Ministry of Foreign Relations. The Ministry of Foreign Relations is responsible for coordinating Chile’s proposals and positions regarding the UNFCCC and ensuring their coherence with the foreign policy established by the President. Other relevant authorities include the ministries of energy, transportation and telecommunications, mining, public health, public works, and housing.

A key advance of the Framework Law (2022) on climate change communication and education is the creation of a national system for climate change information and citizen participation (covered in article 5). This system must include national systems for the inventory and prospective and voluntary certification of greenhouse gas emissions; a climate change adaptation platform; and a climate change scientific repository. It must also ensure participation in decision-making regarding public climate change communication, education and information, and that all public content produced is in accessible language.

Some policies, strategies and plans were a product of public consultations. Through these consultations, observations from civil society were incorporated. These include:

- the 2014 Tax Reform (on specific regulations and implementation of ‘green taxes);

- the 2017-2025 National Climate Change and Vegetational Resource Strategy;

- the 2017 Energy Sector Mitigation Plan.

Chile’s National Strategy on Forests and Climate Change 2017-2025 (2017) defines the national approach to forests and climate change and how they are interconnected. The strategy prioritizes forest conservation and restoration and promotes sustainable forest management practices, carbon sequestration and biodiversity conservation. The strategy also emphasizes forest governance, outlining effective institutional arrangements and coordination between government agencies, local communities, Indigenous groups and private organizations. The strategy also includes monitoring and information systems to address forest conditions, track changes and inform decision-making processes. It also supports the conducting and dissemination of scientific research to inform future strategies and adaptation measures.

The National Action Plan for Sustainable Consumption and Production (2017-2022), developed by the Ministry of the Environment, is organized around four key areas: i) the plan promotes adopting sustainability in public procurement practices and purchases; ii) the plan aims to minimize waste generation, promote recycling and reusing of products, and optimize energy, water and use of materials, in an overall effort to increase resource efficiency; iii) the plan also addresses individual behaviour and consumer choices, aiming to promote sustainable lifestyles and foster behavioural change towards sustainable consumption practices; iv) the plan stresses the importance of collaboration among government agencies, civil society organizations (CSOs), the private sector and academia.

The National Action Plan for Sustainable Consumption and Production (2017-2022) projects a specific cross-cutting action item concerning sustainable lifestyles and education. Concrete actions include enhancing a national environmental certification system for educational establishments; keeping working tables for sustainable lifestyles and education for the public and private sectors; Implementing a dissemination campaign for state-sustainable practices; devising a national sustainable lifestyle education strategy for formal and non-formal entities; and incorporating educational content related to sustainable lifestyles into social projects.

The National Action Plan for Sustainable Consumption (2017) recognizes the importance of raising awareness, disseminating scientific research, and stakeholder engagement. The plan acknowledges that these aspects can contribute positively through fostering understanding, disseminating knowledge, and promoting sustainable behaviours that address challenges posed by climate change.

The Energy Route 2018-2022, published by the Ministry of Energy, outlines the country’s strategies for the energy sector. A key element included in the roadmap is renewable energy expansion, comprising the expansion of renewable energy sources (such as solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal) and targets for renewable energy capacity growth. The route also prioritizes improving energy efficiency across sectors, and diversifying Chile’s energy matrix to reduce its dependence on fossil fuel imports and promote energy security and resilience. The route also calls for decentralized energy generation and developing community-based energy projects that are conducive to energy self-sufficiency and local economic development. There is also an emphasis on fostering collaboration between the public and private sectors to stimulate innovation.

One of the Energy Route’s main components revolves around social inclusion and participation. The route emphasizes the importance of including civil society actors, fostering their informed and active participation in the energy decision-making process, and mobilizing scientific expertise to ensure that energy policies and projects consider the needs, demands and interests of local communities.

One of Chile’s most important policies is the National Climate Change Adaptation Plan (2014). Published by the Ministry of the Environment, the plan aims to develop strategies to enhance Chile’s resistance to climate change as follows: i) the conducting of a comprehensive assessment of Chile’s vulnerability to climate change and the identification of potential adaptation measures; ii) prioritization of the identified adaptation measures; iii) integration of climate change adaptation strategies into the agriculture, forestry, fisheries, energy and infrastructure sectors; iv) capacity-building, stakeholder engagement and knowledge sharing as cross-cutting elements; v) coordination and collaboration among national and sub-national (regional and local) authorities; vi) the establishment of monitoring systems to track progress, evaluate outcomes and identify areas of improvement for future climate change adaptation actions.

The National Climate Change Adaptation Plan (2014) recognizes the importance of raising awareness, knowledge sharing and stakeholder engagement to contribute to national climate change adaptation efforts. The plan also acknowledges the need to engage CSOs, academia and Indigenous communities in adaptation processes by encouraging participation. The plan also highlights the need to disseminate scientific information and best practices to enhance skills and knowledge around climate change adaptation and to integrate climate change considerations into the national education system.

The National Strategy on Forests and Climate Change (2013) emphasizes the importance of raising public awareness, engaging stakeholders and knowledge sharing. The strategy proposes enhancing the public’s understanding of the value of forests and their role in climate change mitigation and adaptation. This should be done by involving local communities, indigenous groups, and civil society organizations in efforts to share information and stimulate dialogues around forest conservation. It also encourages the sharing of knowledge and best practices among governmental and non-governmental entities and agents.

Education and communication

The General Education Law 20.370 of 2009 (last amended in 2010), Curricular Bases and the Curricular prioritization 2023-2025 help to identify climate change education teaching and learning objectives for Chile’s education system.

The General Education Law of 2009 sets out the organization of the whole education system from a constitutional perspective. It highlights ‘sustainability’ as a core value, noting that the system aims to promote respect for the environment. It further notes the sustainable use of natural resources as a concrete expression of solidarity with future generations.

The Curricular Bases are government decrees that formulate learning expectations in each school subject for students throughout their schooling. They were updated in 2018 and retain part of the definitions, curricular concepts and principles that guided the first national curriculum. The Supreme Decree of Education No. 439 of 2012 and the Supreme Decree of Education No. 433 of 2012 established Curriculum Bases for basic education in the listed subjects. The Supreme Decree of Education No. 614 of 2013 and Supreme Decree of Education No. 369 of 2015 established Curriculum Bases from Grade 7 (12-year-old students) to Grade 10 (second high-school grade, 15-year-old students) in the listed subjects. The Supreme Decree of Education No. 193 of 2019 established Curriculum Bases from Grade 11 (16-year-old students) to Grade 12 (17-year- old students). The new-pre-primary curricular bases have been in force from 2019.

In 2020, within the framework of the health emergency caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Curriculum and Evaluation Unit of the Ministry of Education produced a prioritized curriculum, which remained in force until 2022. A diagnosis of the curriculum was carried out to gather evidence to make informed decisions about the priorities. It involved documentary and comparative analysis, implementation follow-up studies, and more than 48 days of dialogues with actors from different educational contexts.

The Ministry of Education then released the Education Reactivation Plan, which aims to promote a comprehensive and strategic response to the educational and socio-emotional needs that emerged in school communities during the pandemic. Resources and policies were focused on the identified priority areas. Based on this process, it was decided that the Update of the Curricular Prioritization would continue to be in force in 2023, 2024 and 2025. The aim would be to facilitate curricular decision-making processes and allow them to be responsive to an evolving context.

The 2023-2025 Curricular Prioritization shows a path for realizing learning objectives of the National Curriculum, in the context of ‘learning reactivation’. This involves prioritizing themes that are present in more than one subject, as well as deepening the learning of them over the years. This is particularly relevant for how climate change would fit into the curriculum. (see section on climate change education at different education levels). With the agreement of 26 October 2022, the National Education Council has made suggestions on the learning objectives by subjects, including the environment.

Article 16 of the Framework Law (2022) refers explicitly to education for climate change. It states that the Ministry of the Environment will promote education and culture on climate change (together with the competent State Administration bodies). The aim is to raise awareness about the causes and effects of climate change, as well as mitigation and adaptation actions. It also mentions that the Long-Term Climate Strategy must include the education of citizens to address climate change, including cooperative action and the fair assigning of responsibilities to encourage community participation. Article 6 refers to how the Long-Term Climate Strategy is to be implemented: i) conducting research on climate change, in accordance with the guidelines proposed by the Scientific Advisory Committee; ii) ensuring the education of citizens to address climate change, including cooperative action and the fair assigning of responsibilities to encourage community participation; iii) creating and strengthening national, regional and local capacities for climate change management; and iv) promoting the exchange of experiences at the national and regional level on mitigation measures and adaptation to climate change at the local level.

The Ministry of Education is responsible for all these functions, and is to work with the Ministry of Science, Technology, Knowledge and Innovation, the Ministry of the Environment and the other competent ministries for these objectives to be realized.

iv. Terminology used for Climate Change Education and Communication

‘Climate change’: Defined in the National Adaptation Plan as ‘an unequivocal fact, caused mainly by man’s actions (...) [generating] a warming atmosphere and oceans, diminishing volumes of ice and snow, rising sea levels, and increasing concentration of greenhouse gasses’ (Ministry of the Environment, 2014: 8).

The website of the Ministry of Education provides a comprehensive definition of climate change, nothing that: ‘Climate change is one of the great challenges we face as humanity. It is understood as a climate change attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and that adds to the natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods. Climate change is a global phenomenon that Chile is not immune to; on the contrary, we are a socially and environmentally vulnerable country. This phenomenon caused by human action is affecting ecosystems and multiple sectors of national activity, in all its areas. The impacts are not only projected at the productive level, in agriculture, forests, water availability, energy generation, fishing, infrastructure, but also at the citizen level, affecting the health and quality of life of Chileans.’

Article 2 of law 19300 of 1994 (amended last through Law 21115 of 2022) defines ‘climate change’ as: change of the climate attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and adds to the observed natural climate variability over comparable periods of time.

The glossary for the science subjects of the curricular orientation for the third and fourth grades of the middle level of education defines ‘climate change’ as: significant variation in the average state of the climate or in its usual variability, which persists for an extended period of time (usually decades or even longer). Climate change can be due to internal or external natural processes, or to changes produced by human activity in the composition of the atmosphere or in land use, causing effects of global scope and of an unprecedented scale in our societies and in the environment.

The glossary for citizenship education, history, geography and social sciences defines ‘climate change’ as: A change in the climate attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and adds to the natural climate variability observed over comparable periods of time, causing global and unprecedented scale effects on societies and the environment, per Article 1 of the UNFCCC.

Law 19300 of 1994 defines ‘environmental education’ as: the permanent process of an interdisciplinary nature, aimed at the formation of a citizenry that recognizes values, clarifies concepts and develops the skills and attitudes necessary for a harmonious coexistence between human beings, their culture and their surrounding bio-physical environment.

‘Education for sustainability’ is defined as: The integration of sustainable development principles into the educational system, to foster a more environmentally conscious and socially responsible society, including elements of civic education, participatory learning, teacher training, and inclusion and equity (Ministry of the Environment, 2020).

‘Sustainable development’ : Article 46 of the framework law of 2022 replaces the content of article 2 of the law 19.300 by defining sustainable development as: ‘the process of sustained and equitable improvement of the quality of life of people, based on appropriate measures of conservation and protection of the environment, considering climate change so as not to compromise the expectations of future generations;’

‘Climate change information’ is defined as: the fundamental right of citizens to obtain timely and relevant information held by public institutions (Congress of Chile, 2008).

v. Budget for climate change education and communication

The Environmental Protection Fund, established in Title V of Law No. 19,300 is mandated to finance specific mitigation and adaptation projects and actions that contribute to confronting the causes and adverse effects of climate change, considering the principle of territoriality. According to Article 36 of the framework law of 2022, the Environmental Protection Fund may finance projects and activities that include capacity-building and strengthening programmes. This would be delivered through education, awareness-raising and dissemination of information, in accordance with the provisions of the Long-Term Climate Strategy, the Nationally Determined Contribution or other climate change management instruments.

According to the 2022 Public Sector Revenue and Spending Budget (2022), Chile’s budget for 2023 is roughly US $83.7 billion. Items specifying the budget allocated to the Ministry of the Environment amount to an expenditure of 1.2 billion CLP (approximately US $1.5 million). They are earmarked for spending on actions relevant to climate change communication and education, including actions related to the implementation of Chile’s Nationally Determined Contribution and the establishment of the country’s national school environmental certification system. Chile thus appears to allocate roughly 0.002% of its national 2023 budget to actions relevant to climate change education and communication. It is important to note that, after reviewing similar sources for the ministries of education, energy, economy, and labour, no relevant climate change communication and education items were identified.

i. Climate change in pre-primary, primary, and secondary education

Chile’s National Curricular Framework (2009) contains several guidelines for climate change education at the pre-primary, primary and secondary levels. The framework includes the environmental impact of a person’s work to be taken into account together with factors such as personal satisfaction, quality, productivity, innovation, social responsibility and a sense of self. The incorporation of the environment into students’ recreational spaces and activities is also noted. It is encouraged that this be discussed alongside other issues such as human rights; mass media; technology; affective life and sexuality; gender, ethnic and religious discrimination; justice; peaceful coexistence; and tolerance. More specifically, Chile’s National Curricular Framework establishes the environment (and care for it) as a minimum obligatory part of the content of subjects such as English (as a foreign language); history, geography and social sciences; natural sciences; and technical-professional training in areas like electricity, mechanics and the visual arts.

Chile underwent a process of curricular prioritization, evaluation and analysis in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Documents related to the 2023-2025 Curricular Prioritization introduce more recent general guidelines for climate change education, including at primary and secondary levels. The Curricular Prioritization for Primary and Secondary Education establishes a general learning objective designed to explain climate change as a global phenomenon. This is to include: different viewpoints about its multiple causes; degrees of responsibility assigned to different actors; and the main consequences of climate change for populations. The policy establishes an additional learning objective that is specifically focused on analysing the impact of different development models and economic policies on daily life and climate change. This is based on the principles of sustainability and ensuring a fair and dignified life for citizens to enable their personal and collective development. The policy also devises a learning objective for modelling the effects of climate change on various ecosystems and their biological, physical and chemical components, and evaluating possible mitigation solutions.

The Curricular Prioritization for Young People and Adults (comprising secondary education levels) establishes care for the environment as a primary goal. The policy discusses the problem of human behaviour in biodiversity and ecosystem equilibrium, conservation and environmental degradation as an overarching learning objective.

The observations recorded in March 2023 of a teacher through a structure developed by the school community within the framework of sustainability and the Citizen Training Plan have been considered as important for refining future interventions. The teacher observed that, although students have some knowledge on climate change, they do not master it conceptually or progressively over time. Learning from previous levels needs to be continuously integrated at subsequent levels; students need to understand that climate change is directly related to human decisions and actions, that they are active at the local level and also linked to the global economy.

Chile has undergone a process of curricular alignment to address gaps such as those that have been identified. The process of curricular alignment establishes new learning objectives for educational levels, spanning the eight levels of basic education and two levels of secondary education. The learning objectives include: recognizing and comparing diverse plants and animals; identifying and communicating the effects of human activity on ecosystems; explaining the importance of adequate resource use; distinguishing renewable and non-renewable natural resources; researching and explaining the positive and negative effects of human activity on glaciers; contrasting diverse natural ecosystems in Chile (such as deserts, highlands, coasts and polar regions); considering criteria such as the opportunities and challenges presented to inhabitation and development; understanding the process of industrialization in the nineteenth century; and analysing the main economic, political and social transformations that Chile experienced after the Great Depression, focusing on salt revenues and import-substitution industrialization.

Climate change is addressed in pre-primary, primary and secondary education in Chile as part of the broader National Environmental Education Strategy (2023), which is spearheaded by the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of the Environment. At the pre-primary, primary and secondary levels, this strategy is mainly conducted through curricular content, environmental learning outcomes, projects and activities including environmental education processes, with components of participation and action.

Climate change is incorporated into the central curricular contents of the following subjects, taught at primary (grades 1–8) and secondary (grades 912) levels: natural sciences (biology, physics, chemistry), history, geography and social sciences, and civic education. These subjects address basic concepts related to climate change, its immediate causes and consequences, as well as elementary measures to mitigate and adapt to its impacts. Environmental learning outcomes promoting knowledge and action about environmental issues – especially climate change – are to be achieved through inquiry and consideration of policies and strategies to adapt and mitigate climate change. Students are evaluated on learning outcomes associated with acknowledging strategies to adapt to Chile’s particular climate challenges. The Ministry of the Environment is responsible for providing suggestions to incorporate climate change concerns and content into Chile’s more recent curricular bases. At the time of writing, the National Public Education Strategy Report did not contain information about the results of these evaluations.

The Ministry of Education provides a comprehensive guide, ‘Digital resources: Early Childhood Education Guide: Valuing and caring for the environment from early childhood’, for early climate change education at the preschool level. The Pre-School Education Guide Valuing and Caring for the Environment since Infancy includes eight themes relevant to environmental care, including: water care; air quality; energy care; residue management; sustainable lifestyles; biodiversity; and disaster risk reduction. From definitions and data provided by the ministry, teaching teams are expected to develop examples and practical activities relevant to pre-school settings. This follows the guidelines established in the Curricular Bases for Pre-School Education (2019), which establishes that pre-schoolers must develop attitudes and abilities to progressively participate in decision-making to embed the values of self-care, solidarity and sustainable development.

The curricular foundations for third and fourth grades at the middle level highlight that: ‘A quality education promotes the development of an active citizenry that defends the values of democracy and freedom, responsible and committed to the present and future challenges of the society; among them, sustainability, climate change, the strengthening of democratic principles and the search for the common good’. Within the subjects of ethical politics, it states: ‘On the other hand, the growing awareness about the current environmental situation in the world, especially with respect to climate change, demands the participation of a citizenry educated in these issues and that possesses the capacity to move towards sustainability.’ Among the learning objectives of the fourth grade at the middle level, the document says: 'Analyse the impact of various development models and economic policies on daily life and climate change, based on sustainability and ensuring a dignified and fair life for all with conditions for personal and collective development.’

Students are also expected to understand: the importance of biodiversity; biological productivity; the resilience of natural systems and how these are being affected by climate change; the introduction of alien species; pollution; and other globally important concepts. Students are expected to be able to: analyse the role of science, technology and society in the prevention, mitigation and repair of the effects of climate change, and in the promotion of sustainable development; develop scientific skills such as analysing, investigating, experimenting, communicating and formulating explanations with arguments; and adopt attitudes that allow them to address contingent problems in an integrated way, based on the analysis of evidence and considering the relationship between science and technology in society and the environment.

The learning objectives of the subjects indicate that students should be able to explain the effects of climate change on biodiversity, biological productivity and ecosystem resilience, as well as its consequences for natural resources, people and sustainable development.

In the area of physics, based on current and historical scientific data, students should be able to: analyse the phenomenon of global climate change; and recognize the observed patterns, probable causes, current effects and possible consequences for the Earth, natural systems and society.

In the area of chemistry, students are expected to be able to explain the effects of climate change at the level of biogeochemical cycles and chemical balances present in the natural system. These include the atmosphere, oceans, fresh waters and soils, and their relationship with sustainable development. Students should also be able to analyse and value the role of chemistry, technology and society in the prevention, mitigation and repair of the effects of climate change. They also need to appreciate the importance of this for the promotion of sustainable development and in the quality of life and well-being of people.

In accordance with the basic orientations for basic and middle level education at the third grade of the middle level, students are expected to: ‘Explain climate change as a global phenomenon, including controversies about its multiple causes, the degrees of responsibility of different actors and their main consequences for the population.’ At the fourth grade of the middle level, students are expected to : ‘Analyse the impact of various development models and economic policies on daily life and climate change, based on sustainability and ensuring a dignified and fair life for all with opportunities for personal and collective development.’

The basic concepts and measures incorporated in the curriculum seek to instil in students an appreciation of the environment, natural resource conservation and sustainable everyday practices. As stated in the Environmental Education Handbook:

[at a basic and medium education level] disciplinary dialogue spaces have been incorporated to enhance the necessary conceptualization of environmental education, incorporating a perspective not only centered upon conservation and protection of the natural environment but also an appreciation of the social and cultural environment, as essential factors to improving people’s quality of life (p. 26).

The participation and action focuses on the practical side of these concepts and outcomes. To this end, students are expected to be involved in community projects, small-scale conservation initiatives and individual actions to promote sustainable lifestyles.

There are different resources available to educate on climate change. educarchile.cl is the Chilean education portal and the product of a mutual collaboration agreement between Fundación Chile and the Ministry of Education. Its website contains classroom resources on climate change for subjects on citizenship education/ environment and sustainability in the third grade of the middle education level. The module focuses on biodiversity in Chile and evaluates the impact of climate change in the country to mitigate the consequences of global warming. The activity involves three steps, with a specific objective and guiding questions. First is the motivation and definition of the problem; then there is an investigation and analysis of a particular geographical area for evaluating the impacts of climate change; and finally, solutions or improvements are presented. The activity draws on the scientific skills of data analysis and the construction of explanations.

ii. Climate change in teacher training and teaching resources

The Ministry of Education is responsible for including climate change in teacher training and pedagogical resources. The ministry aims to prepare teachers to address this effectively, transmitting knowledge and skills to students, through four key aspects :i) teacher training; ii) educational resources; iii) projects and programmes; and iv) collaborative networks. Together with educarchile.cl, the Ministry of Education has designed a course so that teachers throughout the country can learn about climate change. The course takes five to eight hours to complete and is available to all directors and teachers.

The Environmental Education Handbook (2020) notes that the ‘teacher training’ aspect is geared towards teachers’ initial and continuous training in climate change. The aim is to ensure that teachers are able to transmit this knowledge effectively to students. It involves the incorporation into teachers’ training programmes of science in support of climate change, mitigation and adaptation measures, and knowledge regarding ecosystems, biodiversity and sustainability.

Experimento in Araucanía is an example of such a programme. The programme is run in 24 counties with 421 teachers in 194 schools. It offers place-based educational opportunities, transdisciplinary education using non-mainstream sources of knowledge and practical traditions from the region, and value-oriented learning around climate change. Teachers interact with scientists on a one-to-one basis and learn how to build projects, fundraise and improve their schools’ infrastructure. Starting in 2013, the programme has received ongoing support, with a significant leveraging of resources and institutional backing through the Pacific Alliance for STEM education.

Educational resources themselves are key to effective teacher training. The Ministry of the Environment provides guides, teaching material and activity plans, to support teachers in course design for teaching climate change, providing practical approaches and relevant examples for use in the classroom. For instance, Grade 9 students are instructed to develop action-focused research to better understand climate science, and consequently, to think and act in response to the global climate emergency. Students are directed to conduct autonomous research on global warming and climate change and their recent impacts on natural disasters in the country. They are then encouraged to discuss these findings and debate how they (and their country) can act in response to the global climate emergency.

Specific projects and programmes are highlighted for teacher training and educational resources because of their practical orientation. Made available through the Ministry of the Environment’s Eco-Library they include infographics and activity guides. In the Chilean educational system, teachers are expected to develop climate change education programmes and projects, to strengthen students’ knowledge. (Ministry of Education & Ministry of Labour and Social Security, 2020). These can include exchanging experiences, collaborative projects, and further training to enhance teachers’ knowledge and skills around this topic (Ministry of Education & Ministry of Labour and Social Security, 2020).

Collaborative networks are a recent component, and regarded by the Ministry of Education as being very important. Networks and collaboration spaces between teachers and practitioners around climate change and climate education are promoted. The aim is to exchange and consolidate resources, experiences and best practices, and encourage peer-to-peer learning. Examples of how these collaborative networks are being formed with participation or oversight from relevant entities include: ‘Climate Guardians’ (co-sponsored by UNICEF, UNESCO and some Chilean NGOs) or the Columbia Climate Corps Program (co-sponsored by Columbia University, where high school students explore climate complexity in various regions of Argentina and Chile).

The Chilean Strategy for Capacity Building and Climate Empowerment is also a key element of training. This strategy was officially launched in October 2020. It includes promoting the design and implementation of training programmes on environmental and climate change for key public servants and members of the science community. It contains modules on monitoring, control and community involvement. The design and implementation process behind this strategy is projected to be monitored and evaluated every five years.

Specific training programmes have been organized through the initiatives of multiple stakeholders. For example, the Office for Climate Change, together with INNOVEC and ECBI-Chile and with the support of the Siemens Foundation, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs organized a training programme in 2019. The programme was aimed at teachers of different educational levels and included educational sector representatives from Mexico, Colombia, Peru and Chile. The objectives of the training were to promote environmental care and protection awareness; strengthen teaching skills by offering workshops to develop scientific reasoning skills; and establish a critical and proactive attitude to generate individual and collective behavioural changes in school communities.

The Research Centre in Science Didactics and STEM Education of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso (CIDSTEM) delivers the Diploma in Teacher Training in Climate Change. This diploma programme focuses on teachers from different regions, as they are considered to be the direct actors in the transmission of knowledge and practices within environmental education in relation to climate change.

Professionals from the ECBI Program and CR2 of the University of Chile have developed a specific course on climate change for teachers. It is aimed at those teachers who are interested in accessing knowledge, methodological tools and teaching resources to address climate change education in their classrooms, for all school levels. The course has been financed by Siemens Caring Hans and was first offered in the summer of 2023.

The website of the national curriculum offers a climate change guide to support teachers. The guide contains units that cover: what climate change is; the fundamentals of climate science; the worldwide impacts and causes of climate change; policies and institutions that address climate change effects in Chile; climate change mitigation; and how schools and school environments can contribute to climate change action.

iii. Climate change in higher education

According to the Environmental Education Handbook (2020), climate change is also addressed in academic programmes and research in higher education. Three aspects are considered central to the approach to teaching climate change at the higher education level: i) academic programmes; ii) research (including programmes and centres); and iii) community outreach.

In relation to academic programmes, Chilean universities are obliged to offer academic programmes in which climate change and sustainability are cross-cutting components. Examples are the environmental sciences, natural sciences, economics, urban and social studies, and social sciences. Programmes are expected to provide specialized, formal and interdisciplinary instruction to systematically study and address climate change and its impacts. For instance, the Universidad de Chile offers a ‘climate change’ interdisciplinary course, where contents are formulated by scholars from the university’s Climate and Resilience Centre (administered in association with the Universidad de Concepción and Universidad Austral de Chile). The Universidad de Chile also offers a diploma programme in climate change and low-carbon development, through the faculty of physical science and mathematics.

In the area of research, Chilean higher education institutions are expected to fund and conduct research related to climate change in diverse areas such as climate science, adaptation and mitigation measures, impact evaluation and climate policy. To contribute to the body of knowledge and general understanding of climate change, researchers and academics are expected to be provided with enabling conditions for them to carry out their work on projects and the publication of scientific articles. Chile’s higher education institutions are also obliged to: establish and maintain research programmes and centres that are dedicated to the study of climate change and sustainability; and promote interdisciplinary collaboration, applied research, and training or teaching opportunities. Examples are the Climate Science and Resilience Centre administered by the Universidad de Chile, Universidad de Concepción and Universidad Austral de Chile, or the Universidad Santo Tomas’ Climate Change Research Centre.

The Global Change Centre is one of the most important academic initiatives involved in national climate change communication and education efforts. Spearheaded by the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, the centre’s mission is to create and transfer interdisciplinary knowledge, identify needs and generate solutions to train change agents, and contribute to sustainable development. The centre aims to communicate and disseminate results from scientific research and to raise awareness about individual and collective responsibility in climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts.

Community outreach is also considered a crucial component in the Chilean approach to climate change in higher education. To address local and national challenges posed by climate change. higher education institutions are expected to establish ties with communities and stakeholders to promote climate action, including extension activities, collaborations with governmental and non-governmental entities, and knowledge transfer projects. An example is the Experimento in Araucanía, an area with one of the highest concentrations of Indigenous people, who live from forestry, cattle, agriculture and tourism. The project involves Indigenous communities integrating into the programme by supervising activities outdoors with students, such as guided forest walks or birdwatching.

iv. Climate change in training and adult learning

According to the UNESCO-UNEVOC International Centre, the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Economy Development and Tourism, and Ministry of Labour and Social Security are the government entities responsible for developing technical and vocational education and training (TVET) policies in Chile. However, the governance of TVET institutions continues to be decentralized and exercised at a regional level, as there is no national qualification framework in place. Nonetheless, various elements can be extracted from the National Strategy for Vocational and Technical Training (2020).

Specialized training programmes specifically incorporate elements of climate change and sustainability, such as: renewable energies and energy efficiency; environmental management; sustainable construction; architecture; and forestry (Ministry of Education, 2020; Ministry of the Environment, 2020). TVET programmes are also encouraged to include content related to climate change in specific areas. In this way, students may acquire knowledge about the impact of climate change in different sectors, as well as various mitigation and adaptation measures. The development of projects that address climate change and that are geared towards energy efficiency and sustainable systems is encouraged. Strong connections between these programmes and productive sectors in Chile’s economy and relevant industries are also encouraged. The aim is for students to undertake internships and projects within organizations where knowledge of climate change mitigation and adaptation is applied. Due to the decentralized governance of TVET institutions nationally, at the time of writing there was no readily available information on the concrete implementation of these policy directives.

i. Climate change and public awareness

Chile’s Fourth National Communication (2021) includes information related to public campaigns and initiatives concerning climate change. The intention is to increase public engagement, understanding and participation.

In terms of awareness programmes, the National Communication outlines programmes that target schools, communities, Indigenous groups and industry. The programmes provide information on the impacts of climate change, and the importance of collective action and behavioural changes in contributing to mitigation and adaptation measures. At the same time, the communicative strategies included in the National Communication include the use of traditional mass media outlets and social media, the websites of national government departments and agencies, and public events around the country. The aim is to transmit accurate and accessible information on climate change.

Some relevant examples mentioned in the document are: i) @reciclorganicos and #YoReciclOrganicos campaigns on social media to raise awareness about converting organic residue into clean energy and natural fertilizers and climate change mitigation, spearheaded by the Ministry of the Environment and launched in 2018; ii) the Ministry of Energy’s Technical Assistance Unit’s campaign for small- and medium-sized enterprises seeking to increase their energy efficiency carried out on social media platforms; iii) monitoring of climate variables and meteorological information through radio and social networks, to support local fishing, aquatic sports and maritime activities; and iv) dissemination of the agreements reached and initiatives supported in COP25 through the Ministry of the Environment’s Climate Change line of action website and social media.

The Nationally Determined Contribution (2021) addresses an important capacity-building component, which describes training programmes, workshops and national educational resources for empowering individuals and communities to take informed action on climate change. These include promoting the design and implementation of training programmes on environmental and climate change for key public servants and members of the science community, with modules on monitoring, control and community involvement. This effort was formalized under the Chilean Strategy for Capacity Building and Climate Empowerment, which was officially launched in October 2020, and whose design and implementation process is projected to be monitored and evaluated every five years.

The Ministry of the Environment is the main government agency responsible for public awareness on climate change. According to its Climate Change line of action, through the Environmental Education and Citizen Participation Division, the ministry is responsible for improving public knowledge on climate change. The ministry has developed resources such as the Climate Digital Base, which publishes detailed information about the country’s greenhouse gas emissions by sector.

The part of the website of the Ministry of Education that deals with climate change includes a series of eight educational components, as part of the framework of the European Union's support for the Chilean presidency of COP25. Eight two-minute videos explain key concepts related to climate change, including how to address it, and with a call to action show what people can do to take care of our planet.

The Environmental Interschool is an initiative developed by the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of the Environment and social enterprise organization Kyklos to encourage the participation of educational communities to care for the environment, and to develop key skills for children and young people through educational activities. The interschool consists of a digital network dedicated to providing tools to educational communities to develop environmental education and improve the school climate through a range of projects, activities, contests and challenges related to environmental issues.

The educational material can be accessed through a mobile application, a digital platform and social networks. To date, 1,768 activities (such as recycling) have been completed by the organizations in the action network. This is also a way of achieving personal and social skills, such as academic self-esteem and motivation, participation and citizenship, healthy living habits and climate awareness. These are all included as personal and social development indicators in SIMCE, which monitors the quality of education in the country. Currently, 3,900 schools are participating in this initiative.

ii. Climate change and public access to information

The National Communication (2021) highlights Chile’s commitment to ensuring public access to climate change-related information and data. Three action areas are mentioned: transparency; data sharing; and public engagement.

The National Communication (2021) reiterates Chile’s commitment to ensuring accessible and transparent information about climate change-related impacts and policies. This information is available to the public through the Ministry of the Environment’s Climate Change microsite.

In terms of transparency, Chile’s National Communication and Nationally Determined Contribution emphasize the timely disclosure of greenhouse gas emissions data, climate policies and measures, adaptation plans, and progress reports on national implementation. An example is the National Climate Change Action Plan 2017-2022, which calls for a 30% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, and the reforestation of 100,000 hectares of forest. The documents also point to the ongoing efforts to update and maintain the national climate change website. The website contains reports, publications, open datasets and educational materials for better understanding and public awareness of climate change. At the time of writing, however, the progress reports were not accessible.

Regarding data sharing, both the National Communication and Nationally Determined Contribution emphasize Chile’s commitment to initiatives that make climate change-related datasets publicly available. They also refer to the need for ongoing dissemination of scientific research and studies on climate change and its impacts, such as through providing links on the Ministry of the Environment’s Climate Change line of action website.

Regarding public engagement, the National Communication and Nationally Determined Contribution refer to the opportunities for the Chilean public to actively participate, provide input and shape climate change actions and policies. The ‘Citizen Consultations’ run by the Ministry of the Environment are an example: the ministry presents environmental regulatory instruments that have been proposed, and on the basis of citizens’ opinions and observations, the ministry is expected to modify the instruments. Between 2013 and 2023, 114 consultations were conducted.

Chile’s National Adaptation Plan (2014) and Framework Law (2022) call for the establishment and leveraging of a web of national and regional consultation committees, where citizens can participate in climate policy design, implementation and monitoring. In response, in January 2021, the Environmental Education and Citizen Participation Division of the Ministry of the Environment approved an official Guide for the Implementation of Citizen Consultation Processes. At the time of the guide’s publication, 73 consultations had already been conducted. These were around themes such as species classification, modifying decontamination plans, drafting electromagnetic radiation emission legislation, and national species recovery and conservation plans.

iii. Climate change and public participation

Public participation is a substantial component of the Fourth National Communication (2021). The National Communication highlights the inclusion of public consultations at various stages of the design and implementation of national and sub-national climate change measures and policies. The document describes planning and deliberation processes and spaces, where civil society stakeholders can express their views, provide input and contribute to decision-making. The National Communication reaffirms Chile’s commitment to liaise with stakeholders such as CSOs, Indigenous communities, industry, academia and local governments during the processes of deliberation.

This element of National Communication reflects a practice that has already been developed by the Chilean Government. Some policies, strategies and plans that have incorporated public consultations and observations from civil society include:

- the 2014 Tax Reform (on specific regulations and implementation of ‘green taxes’);

- the 2017-2025 National Climate Change and Vegetational Resource Strategy;

- the 2017 Energy Sector Mitigation Plan.

To conduct the participation process, relevant government agencies first developed a citizen participation plan that outlined the stakeholders and the terms of reference; they then received observations, evaluated whether they were admissible; and then publicized the results, by notifying stakeholders and citizen groups who participated in the first stage, and releasing official reports . However, it was only in January 2021 that a specific process for the implementation of a Citizen Consultation Processes for environmental education and the modification of environmental regulatory instruments and that was published in official reports was introduced.

Chile’s Nationally Determined Contribution (2020) also outlines programmes that aim to provide knowledge, skills and resources to individuals and CSOs to actively engage governmental agencies and international actors in climate change-related decision-making processes. An example is the Strategy for Capacity Development and Climate Empowerment, implemented in 2021. This promotes citizen participation as well as that of vulnerable communities in the development of climate change policies, programmes, plans and actions. It also requests the public provision of climate change information to facilitate the design and implementation of appropriate local actions.

In terms of participation, Chile’s National Adaptation Plan (2014) establishes the promotion of citizen participation in the process of climate change adaptation as one of its key principles. The plan calls for the establishment of a central consultation committee and regional consultation committees and for citizens’ involvement in the design, implementation and monitoring of climate change adaptation policy. These committees are also mentioned in Chile’s 2022 Framework Law, as the legal structures for citizen participation.

Article 5 of the framework law states that the Ministry of the Environment, together with the sectoral authorities indicated in article 17 are responsible for the preparation of the Long-Term Climate Strategy. The relevant ministries and agencies must include a stage of citizen participation (to last 60 working days) as well as reports written by the Scientific Advisory Committee for Climate Change and the Council of Ministers for Sustainability and Climate Change.

i. Country monitoring

The Chilean Government describes institutional measures and the development of indicators to monitor the implementation of all the policies, strategies and plans outlined above. Two documents refer to the measures for monitoring the progress of their implementation: the 2023 SDG Voluntary National Report and the Framework Law (2022).

The SDG Voluntary National Report outlines the results of a monitoring process applied to 669 public programmes, which was implemented until 2021. The monitoring process found that, of the 669 programmes analysed, 574 were linked to the SDGs. It was found that these programmes linked to two or more SDGs simultaneously, for instance, under poverty reduction or inequality mitigation frameworks, or accessible and non-contaminating energy, industry, innovation, infrastructure, submarine life, climate action and alliances. However, the fact that 18.68% of the public programmes were not linked to the SDGs was identified as an area of potential improvement:

Among the achievements for SDG 4 and SDG 13 listed in the Voluntary National Report are:

- Environmental workshops for youths, employing an Indigenous approach (SDG 4)

- Production of environmental teaching material for youths, emphasizing local ownership (SDG 4)

- Participation in COP27, where Chile reinforced its commitment to the Paris Accords (SDG 13)

- The Youth Climate Ambassadors initiative, which under the direction of Chile’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs selects 30 Chilean youths to participate in international climate negotiations and dialogues with the country’s national negotiating team to the UNFCCC (SDG 13).

In terms of institutional mechanisms, the Voluntary National Report highlights the creation of the National Council for the Implementation of the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. The council is made up of the ministers of foreign relations (spearheading the council), social and family development (overseeing the technical secretariat), economy, environment, and the president’s chief of staff. The council advises the president and coordinates the implementation and monitoring of policies linked to the 17 SDGs. The council includes an intersectoral working group, a national network for the 2030 SDG agenda, and a specific group in charge of developing indicators to monitor progress and compliance with the SDGs.

The Voluntary National Report highlights the Ministry of Energy’s responsibility for promoting sustainable industrialization. The report notes that the different measures taken by the Ministry of Energy have resulted in a slight decrease in the country’s CO2 emissions. The report focuses specifically on 2014 and 2020 as the years with the lowest emissions registered in the 1990-2020 period, and stresses the commitment to continued monitoring of this indicator.

The Framework Law (2022) demands the creation of monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) indicators in all national and local policy instruments. For future local-level policy instruments, such as communal climate change action plans, and national-level policy instruments, such as the greenhouse gasses prospective national system, the Framework Law specifically states the need to incorporate ‘monitoring, reporting, and compliance verification indicators, to ensure the fulfilment of [the] measures’.

The Ministry of the Environment is responsible for monitoring activities which simultaneously support local industries. An example is the monitoring of climate variables and meteorological information through radio and social networks, to support local fishing, aquatic sports and maritime activities. These activities are conducted through the ministry’s Climate Change line of action.

ii. MECCE Project Monitoring

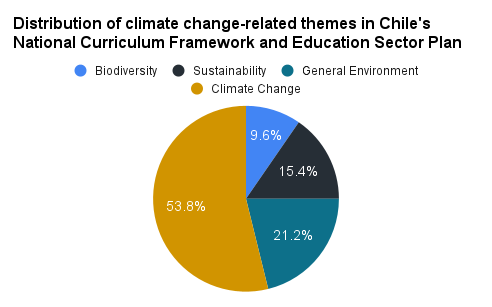

The MECCE Project Axis 2 team conducted a systematic search of references in Chile’s National Curricular Framework, relative to biodiversity, sustainability, climate change and the environment. The Axis 2 team found 52 references : (a) 5 ‘biodiversity’ references; (b) 8 ‘sustainability’ references; (c) 11 references to ‘the environment’; and (d) 28 references to ‘climate change.’

This section will be updated as the MECCE Project develops.