CLIMATE CHANGE COMMUNICATION AND EDUCATION

2. Climate change education and training in the country

3. Climate change communication in the country

i. Climate change context

Australia has a federated governance system, in which its six states and two territories influence the development of national policy related to climate change communication and education initiatives. The country’s constitutional mandate to protect the environment lies with the states. Each state and territory has their own departments, strategies, and agencies relating to climate change and education, and partially also to communication. However, state-level initiatives are tied to national approaches, such as the Australia Curriculum in formal education. This country profile provides information on Australia’s approach to mainstreaming climate change communication and education on a national level. It gives examples of state-level initiatives only when relevant and reported by the country in its official communications.

Australia is the 6th largest country globally by area. However, its population is concentrated in urban areas close to the coast. Australia is vulnerable to extreme climatic events including extreme heat, floods, wildfires, and drought. According to the World Bank, key areas in Australia impacted by climate change are water security, agriculture/food security, housing, and infrastructure.

According to the Global Carbon Atlas, Australia is a high-emitting country. Despite its relatively small population of approximately 25.5 million, it emitted 15 t CO2 per person in 2020. The highest emitting sector in Australia, according to the 7th National Communication (2017) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), is the energy sector, largely due to fossil fuels that accounted for nearly 80% of emissions in 2015. Next highest emitting sectors are agriculture at 13% and industrial processes and product use at 6%.

Australia is designated by the UNFCCC as an Annex I (industrialized) country. Australia signed the Kyoto Protocol in 1998 but did not ratify it until 2007. Australia signed and ratified the Paris Agreement and accepted the Doha Amendment in 2016.

The world’s first climate emergency declaration was by an Australian local council area in 2016. By early 2021, over 100 local councils, the Australian Capital Territory Legislative Assembly, and the South Australian Upper House declared climate emergencies. This means that over one-third of Australia’s population lives under a climate emergency declaration, despite the federal government not approving a Climate Emergency Declaration Bill in December 2020.

Australia includes many distinct groups of Indigenous Peoples with their own languages, cultures, and traditions. According to the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, care for Country (the land, waterways and seas with which groups of First Australians have a traditional relationship) “is based in the laws, customs and ways of life that Indigenous people have inherited from their ancestors and ancestral beings” (2011, p. 1) and is an integral part of life for Indigenous Peoples across Australia. In some states, Indigenous knowledges are part of climate change communication and education, such as through the National Indigenous Dialogue on Climate Change (2021).

ii. Relevant government agencies

Climate change

Several government departments share responsibility for climate change issues. Accountability is shared between the federal government, state and territory governments, and local governments. An assessment report on the State of the Australian Environment (2016) details the system.

The different roles and responsibilities were set in 2012 by the Council of Australian Governments’ Select Council on Climate Change. According to the National Resilience and Adaptation Strategy 2021–2025 (2021), the Australian government is responsible for “significant investments in public infrastructure, and providing national climate science and information” (p. 14). The states, territories, and local governments focus on local and regional challenges.

Within the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, the National Adaptation Policy Office is responsible for climate change adaptation and climate science policy and programs, and the Emission Reductions Division is responsible for Australia’s emissions reductions efforts. The Department was established in early 2022 and is the main agency in charge of climate change in the country.

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water works with several agencies and organizations on climate change initiatives, with a strong focus on energy regulation. The Australian Energy Infrastructure Commissioner manages complaints about wind farms, large-scale solar farms, energy storage facilities, and new major transmission projects. The Australian Renewable Energy Agency finances low-emission technology and renewable energy projects. The Clean Energy Finance Corporation finances clean energy projects.

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, together with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, is responsible for Australia’s engagement with international agreements and negotiations, including with the UNFCCC. Australia’s Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE) Focal Point is located within the International Climate Negotiations Branch of the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Climate change communication and education projects and programs stem from that Department, such as the National Environmental Science Program.

The Climate Change Authority advises the government on Australia’s climate change policies and future emissions reduction targets. The Authority is an independent statutory body established by the federal government under the Climate Change Authority Act (2011) to provide expert advice on climate change mitigation initiatives to the Australian government. Specifically, the Authority conducts regular commissioned reviews and climate change research. The Authority also produces climate change fact sheets to inform the public.

The Clean Energy Regulator measures, manages, reduces, or offsets Australia's carbon emissions. It is an independent statutory authority established in 2012 by the Clean Energy Regulator Act (2011). It administers the legislative framework underpinning the Australian government’s approach to its targets, including the Emission Reduction Fund of Australia, the Renewable Energy Target, the National Greenhouse and Reporting Scheme, and the Safeguard Mechanism. The Regulator monitors compliance with climate change laws, including the Emission Reduction Fund. The Regulator assesses whether education or enforcement action is necessary by collecting information, conducting independent audits, and undertaking inspections.

The National Emergency Management Agency was established in 2022 to ensure that Australia would be able to respond adequately to emergencies.

Other agencies associated with the government, such as the Bureau of Meteorology and the Commonwealth Science and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), have responsibilities for collecting, analyzing, and communicating climate data. The CSIRO uses climate simulations to project future climate. The states have their own Environmental Protection Agencies.

Education and communication

In Australia, the state and territory governments are responsible for many aspects of education and most of the education funding. Legislation in each state makes schooling compulsory for children aged 6 to 15 or 16 years. Each state and territory has its own Ministry of Education, which must follow general guidelines established on the federal level. All education policies in Australia must consider the right to education as defined in several United Nations conventions, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights.

The Department of Education is responsible for education, including primary, secondary, and higher education at the national level. The Australian Curriculum is overseen by the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. Sustainability is recognized as a cross-curriculum priority that connects and relates relevant aspects of content across learning areas and subjects for students studying from Foundation to Year 10. All states and territories are required to teach the Australian Curriculum, which was reviewed in 2020–2021 to ensure that it remains world-class and to strengthen connections in learning areas to the cross-curriculum priorities. The updated Foundation to Year 10 Australian Curriculum (Version 9.0) is available on a new Australian Curriculum website. The new curriculum will be implemented from 2023.

The Education Ministers Meeting is generally held four times a year for collaboration and decision making on early childhood education and care, formal education, higher education, and international education.

The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations is responsible for skills and training.

iii. Relevant laws, policies, and plans

Climate change

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999) is Australia’s primary federal environmental legislation. The Act’s main objective is to protect and manage matters of national environmental significance. The Act mentions Australia’s obligations to climate change-related agreements such as the UNFCCC.

The Climate Change Authority Act (2011) established the Climate Change Authority, which is required to conduct reviews under 1) the Clean Energy Act (2011), 2) the Carbon Credits (Carbon Farming Initiative) Act (2011), and 3) the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act (2007). The Authority also conducts research in matters related to climate change. The Climate Change Authority Act established the Land Sector Carbon and Biodiversity Board, which advises the Minister for the Environment, the Climate Change Minister, and the Agriculture Minister about climate change measures that relate to the land sector.

On 13 September 2022, the Climate Change Bill 2022 and Climate Change (Consequential Amendment) Bill 2022 became law. These Climate Change Acts:

- legislate Australia’s updated Nationally Determined Contributions (2022) of 43% emissions reduction below 2005 levels by 2030 and net zero emissions by 2050

- task the Climate Change Authority to assess and publish progress against these targets and advise the government on future targets, including the 2035 target

- require the Minister for Climate Change to report annually to Parliament on progress in meeting national targets

- embed the national targets in the objectives and functions of a range of government agencies, including the Australian Renewable Energy Agency, the Clean Energy Finance Corporation, Infrastructure Australia, and the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility.

Australia’s first National Climate Change Adaptation Framework was released in 2007. In 2021, Australia’s Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment released an updated National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy for 2021–2025, replacing the previous iteration of the Strategy from 2015. The 2021 Strategy notes the importance of the education sector and of providing authoritative climate information in adapting to climate change. It builds on four domains—natural, built, social, and economical—to help Australia prepare for climate change. Three objectives are at the core of the Strategy: drive investment and action through collaboration, improve climate information and services, and assess progress and improvement over time. The 2021 Strategy also focuses on Indigenous knowledges through the National Indigenous Dialogue on Climate Change.

Australia has a number of strategies to reduce emissions. These include the Emissions Reduction Fund, the Safeguard Mechanism, the Climate Solutions Fund, the Renewable Energy Target, measures for energy production and fuel standards, and the Long-Term Emissions Reduction Plan (2021). Nevertheless, the Climate Action Tracker rated efforts up to 2022 as insufficient.

Most states and territories have their own environmental protection acts and climate change policies to supplement federal legislation, including the Australian Capital Territory’s Climate Change and Greenhouse Gas Reduction Act (2010), Queensland’s Environmental Protection Act (1994), South Australia’s Climate Change and Greenhouse Emissions Reduction Act (2007), Tasmania’s Climate Change (State Action) Act (2008), ACT (Australian Capital Territory) Climate Change Strategy 2019–2025, and Victoria’s Climate Change Act (2017). Some states are more progressive in climate change legislation.

As an example, the Climate Change Act 2017 gives Victoria state the legislative foundation to manage climate change risks, maximize opportunities that arise from decisive action, and drive a transition to a climate-resilient community and economy with net zero emissions by 2050. It addresses the majority of the commitments set out in the Victoria government’s response to the 2015 Independent Review of the Climate Change Act 2010. Victoria’s energy and climate change initiatives include Victoria's Climate Change Framework and Victoria's Renewable Energy Action Plan.

The ACT (Australian Capital Territory) Climate Change Strategy 2019–2025 outlines the next steps that the community, business, and territorial government will take to reduce emissions by 50%–60% (below 1990 levels) by 2025 and establish a pathway for achieving net zero emissions by 2045. The Strategy coordinates with the ACT Planning Strategy (2018), the ACT Housing Strategy (2018), and the draft Moving Canberra: Integrated Transport Strategy. Together, these strategies provide a comprehensive approach to building a net zero emissions city. Canberra's Living Infrastructure Plan: Cooling the City complements the ACT Climate Change Strategy, which sets the direction to keep Canberra cool, healthy, and livable in a changing climate.

Education and communication

The Australian Education Act (2013) sets out the rights and responsibilities of organizations in order for them to receive Australian federal government funding for school education. The Act also sets the broad expectations for compliance to ensure funding accountability to the federal government and school communities. The Australian Education Regulation (2013) enacted under the Australian Education Act (2013) requires schools to deliver the Australian Curriculum, which includes the cross-curriculum priority of sustainability.

The federal government also implements the Higher Education Support Act (2003), which aims to support the higher education system to be equitable and diverse, to contribute to Australian research capabilities and cultural/intellectual life, and to be appropriate to meet Australia’s social and economic needs for a more highly skilled and educated population. Climate change is not part of this Act.

The Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians (2008), developed by all of Australia’s education ministers, refers to climate change and the embedding of sustainability across the curriculum. Its preamble states that “Complex environmental, social and economic pressures such as climate change that extend beyond national borders pose unprecedented challenges, requiring countries to work together in new ways.” The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration (2019) does not refer directly to climate change. However, that Declaration does maintain a focus on preparing young people “to thrive in a time of rapid social and technological change, and complex environmental, social and economic challenges” (p. 2).

The 2009 National Action Plan, Living Sustainably: Government’s National Action Plan for Education for Sustainability, has no statutory power and its application was not mandated. The Plan did not explicitly address climate change education but incorporated the topic within the broader theme of sustainability. The Plan highlighted that “The national advisory council, network and research program established under the first Plan (released in 2000) have played, and will continue to play, an important role in guiding education for sustainability in Australia” (p. 11).

The Australian Curriculum is for primary and secondary education in Australia. The Foundation to Year 10 (F-10) Curriculum has guided schools in all states and territories since 2014. The Curriculum contains eight learning areas (or subjects) in which students develop disciplinary knowledge, skills, and understanding. The cross-curriculum priority of sustainability, which includes climate change, connects and relates content across all learning areas and year levels.

The Department of Education’s National School Reform Agreement (2018) is a joint agreement between the federal government, states, and territories to improve student outcomes across Australian schools. The actions in the agreement include high-level issues such as teacher workforce needs, assessment, and improving national data on student achievement, rather than the delivery of education about particular subjects (such as climate change).

The former Department of the Environment and Energy developed the Climate Compass: A Climate Risk Management Framework (2018) to help Australian public servants understand climate change risks and manage the challenges properly. It includes step-by-step instructions on approaching climate change. Understanding how climate change is communicated is one of the first steps in the Framework.

Climate change policies of state and territorial governments integrate some elements of climate change communication and education. For example, the Queensland Climate Adaptation Strategy (2017) identifies “People and Knowledge” as one of four pathways in climate adaptation, to “Empower best-practice climate science, education, and engagement to support climate risk management within Queensland’s communities” (p. 17). The Northern Territory’s Delivering the Climate Change Response: Towards 2050 – A Three-Year Action Plan for the Northern Territory Government (2020) has an objective to inform and involve its citizens in the climate change response. South Australia’s South Australian Government Climate Change Action Plan 2021-2025 (2020) and Directions for a Climate Smart South Australia (2019) both emphasize accessibility of information. Tasmania’s Climate Action 21 climate change action plan (2017) identifies “supporting investment in skills to prepare for a changing climate” as an essential element of growing a climate-ready economy” (p. 16). Victoria's Climate Change Strategy (2021) lists capacity building and partnerships as a priority area, including the need to “incorporate climate change considerations into education, training and re-skilling of the workforce” (p. 44). Other states and territories have some references to climate change communication and education in their plans.

Australia’s climate change commitments have a strong focus on supporting developing countries. For example, its Submission on Strategies and Approaches for Climate Finance 2015-2020 (2018) aims to improve education on climate change in the Pacific region. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s Climate Change Action Strategy 2020-2025 lists specific examples of climate change education in Kiribati and for Pacific women, but does not otherwise focus on climate change communication and education.

In terms of training and vocational education, Australia held a Jobs and Skills Summit in 2022. The outcome document aims for more clean jobs that will help Australia to have a cleaner economy. The document also calls for better reporting of “climate and nature related financial risks” (p. 13).

iv. Terminology used for Climate Change Education and Communication

The Australian Curriculum (2022) considers climate change within the cross-curriculum priority of sustainability, which is taught in units across Foundation to Year 10. It states:

Sustainability addresses the ongoing capacity of Earth to maintain all life. Sustainable patterns of living seek to meet the needs of the present generation without compromising the needs of future generations.

Actions to improve sustainability may be individual or collective endeavours shared across local, national and global communities. They necessitate a renewed and balanced approach to the way humans interact with each other and the environment. Actions should reflect values of care, respect and responsibility, and require individuals and communities to recognise, adapt to and manage change.

Young people require the knowledge and skills to engage with contemporary issues such as climate change, biodiversity loss, equitable access to resources, and preservation of cultural and language diversity. They are looking for social, economic and political models that provide solutions to these issues. (n.p.)

Terms used in previous government documentation include ‘environmental education’ (Environmental Education for a Sustainable Future: A National Action Plan; 2000), ‘environmental education for sustainability’ (Educating for a Sustainable Future: A National Environmental Education Statement for Australian Schools; 2005), and ‘education for sustainability’ (Living Sustainably: The Australian Government’s National Action Plan for Education for Sustainability; 2009).

‘Disaster resilience education’ is another term used. The Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience, in its Education for Young People document (n.d.), defines disaster resilience education as “learning about natural hazards in the local environment and ways to keep communities safe from harm before, during and after an emergency or disaster” (n.p.) This includes to “explore global issues of sustainability and climate change from a local perspective.”

The terms that Australia uses in its documents (e.g., 7th National Communication; 2017) for climate change communication and education include ‘climate change education,’ ‘climate science/change and sustainability education,’ and ‘public awareness, understanding, and participation in addressing climate change.’ This terminology has clear links to Action for Climate Empowerment documentation.

Many states use the term sustainable schools. In Western Australia, this term refers to a “whole-school planning framework for Education for Sustainability that has been developed 'by schools, for schools” (n.p.) to support implementation of the Western Australian Curriculum.”

Indigenous knowledges are also used in terminology. One example in the 2015 National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy is that “fire is a significant part of Indigenous cultures, and skillful burning of landscapes by Indigenous Peoples has informed early season bushfire management, reducing the damage caused by large intense bushfires” (p. 9). The updated 2021 National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy notes the importance of blending “traditional weather and climate knowledge” with western climate change science to address the climate crisis (p. 25).

v. Budget for climate change education and communication

As a function of the Australian Commonwealth Government’s general government expenses, education spending is estimated to be US$ 28,963 (AUD 44,788 million) in 2022–2023, which is 7.1% of total government spending (Commonwealth of Australia, 2022). The budget does not indicate the percent of this funding that goes toward particular learning areas such as climate change education.

Australia’s 2021-2022 budget outlined a gas-fired recovery from the impacts of COVID-19. The budget includes some climate-friendly spending, such as US$ 914 million (AUD 1.2 billion) to “establish Australia at the forefront of low emissions technology innovation;” US$ 76 million (AUD 100 million) to “protect our sea life, restore coastal ecosystems, reduce emissions and enhance management of ocean;” and US$ 154.5 million (AUD 209.7 million) for an Australian Climate Service. However, many found the budget’s climate investment insufficient (The Guardian, 2021; The Conversation, 2021; The Climate Council, 2021). The Global Recovery Observatory found that only 1.8% of Australia’s COVID-19 recovery spending (US$ 99.8 billion; AUD 131.06 billion) was dedicated to green projects. No information is available to indicate how much spending is dedicated to climate change communication and education.

Climate program funding is available to climate initiatives, including emissions reduction. Funding comes from a number of sources, both government and non-governmental. Much of this funding focuses on supporting innovation and new technologies. Governments at the state, territory, and local levels also provide grant funding for adaptation and mitigation activities, including education, communication, and skills-building programs. However, it is unclear how much of this funding is directed toward climate change communication and education.

State-level funding for climate change communication and education does exist. For example, Victoria allocated US$ 185 million (AUD 250 million) in its 2021–2022 budget to environmental protection, including climate change.

i. Climate change in pre-primary, primary, and secondary education

Australia’s National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy (2021) states that "adaptation action and resilience building require a coordinated and collaborative effort across all levels of government, businesses and a wide range of organizations, including those with responsibilities for... education” (p. 21). However, the Strategy includes little about formal education.

The Australian Curriculum guides schools across the country. All states and territories use the Foundation to Year 10 curriculum. The Curriculum also contains cross-curriculum priorities, which are broad issues featured within learning areas and content descriptors. The three cross-curriculum priorities are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures, Asia and Australia’s Engagement with Asia, and Sustainability. These priorities can be found in content descriptors across the entire curriculum. Education for sustainability within the Australian Curriculum involves knowledge attainment and planning action, demonstrating that it is cognitive and action oriented.

The inclusion of elaborations (content descriptors) related to climate change assists teachers to decide where this content is best taught in their local context. This structure does not restrict the way the curriculum can be enacted in a school. The cross-curriculum priority of sustainability can be addressed through a number of learning areas, including Science, Humanities and Social Sciences, (HASS) and Technologies. The elaborations help teachers identify the opportunities and then plan their teaching and learning programs.

The Science and Humanities and Social Sciences curricula include important concepts and content that students must learn. Students can then apply their knowledge and skills to understand climate change. For example:

- In Science, the Earth and space science sub-strand develops the core concept that Earth’s systems are dynamic and interdependent. Interactions between the systems cause continuous change over a range of scales. Climate change is a key change to the Earth system that can be modeled by examining processes and interactions between Earth’s spheres.

- In Foundation to Year 6 Humanities and Social Sciences, the focus is on understanding the world students live in, past and present. In Years 7–10 Geography, the focus is on deepening student understanding of why the world is the way it is and the interconnections between people, places, and environments over time.

- In both subject areas, students apply concepts such as ‘change’ to understand a particular challenge, issue, or event.

Some references to climate change can be found in content descriptors across the Curriculum. The MECCE Project monitoring section of this profile (section 4.II) describes the keywords related to climate change that are discussed in the Curriculum. In particular, the cross-curriculum priority of sustainability allows educators to teach about climate change. For example, one organizing idea is that sustainable patterns of living rely on the interdependence of healthy social, economic, and ecological systems. Such ideas are available throughout all subjects and aim to encourage knowledge, skills, values, and world views necessary to contribute to more sustainable patterns of living.

The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia (2009) guides learning in pre-primary education. The Framework does not explicitly mention climate change. However, one key outcome is that “children are connected with and contribute to their world” and “become socially responsible and show respect for the environment” (p. 32). This approach lays a foundation on which later schooling can build.

At Senior Secondary level (Years 11 and 12), students have the flexibility to choose subjects, with a wide range of offerings available, including Earth and Environmental Sciences, Physics, Biology, and Geography. Curriculum for these subjects includes several mentions of climate change and related topics. Students learn about the causes of climate change, climate justice, and what they can do to slow climate change.

The Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience launched the Education for Young People Program, to teach young Australians how to deal with disasters. The Program provides resources for teachers, establishes regular awards for students, and connects people across regions.

Some states have developed specific measures to understand how climate change education can be embedded into schools. Queensland organizes an Environmental Sustainability Forum each year, which includes climate change education. The New South Wales Department of Education provides a resource for teachers with the main outcomes of the syllabus on climate change. In Victoria, the Victorian Curriculum F-10 identifies resources on climate change across all levels of education. The Department of Education and Training Victoria has procured interactive education resources to support learning throughout the curriculum, through ClickView across all Victoria government schools and through Stile for students in Years 7 to 10 and secondary teachers. In Western Australia, the Western Australia Department of Education has a curriculum resource module on “Climate calculations” for Year 7.

Australia’s 7th National Communication (2017) reported that four states developed climate change education programs: Queensland, New South Wales, Western Australia, and Victoria. The programs are Queensland Sustainable Schools, Sustainable Schools New South Wales, Sustainable Schools Western Australia, and ResourceSmart Schools in Victoria. According to the National Communication (p. 181), “Approximately 63 percent of [New South Wales] schools, 75 percent of Queensland schools, and 46 percent of [Western Australia] schools are participating” in state-developed climate change education programs. All programs strongly focus on education for sustainable development and the whole-school approach, with climate change embedded in the programs.

ii. Climate change in teacher training and teaching resources

Universities choose whether to integrate climate change education into their pre-service teacher training programs. Teachers and schools choose whether to seek further professional development in this area. The Accreditation of initial teacher education programs in Australia: Standards and Procedures (2018) does not provide specific detail about the type of content that should be included in an initial teacher education degree and makes no mention of climate change, sustainability, or environmental education. The Australian Professional Standards for Teachers, while identifying the importance of knowing content and how to teach it, donot specifically highlight the importance of integrating climate change, sustainability, or environmental considerations into teaching practice.

Resources for in-service teachers are rolled out through the Sustainable Futures education program developed by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). The program supports primary and secondary teachers for Years 3 to 10. Teachers who register with the program receive free access to digital teaching resources, including ideas and activities to support teaching of sustainability and the environment in Australian schools. According to the Report on the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (2018; SDGs) by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 814 schools have participated.

Some states do have exclusive resources for climate change education. For example, the New South Wales AdaptNSW resources and the Sustainable schools website contain a wealth of climate change education resources for both teachers and students. The Victoria government’s climate change portion of the FUSE education resource site also offers resources. The competencies covered by this teacher training are cognitive (empowering teachers with the knowledge to teach climate change education) and action/behavioral (encouraging teachers to adopt more environmentally friendly practices in their schools). Such practices collectively have saved participating schools USS 2.5 million (AUD 3.4 million) as of 2016. Renewables, Climate and Future Industries Tasmania provides resources for schools and teachers specifically on action for climate change. Many of these resources are from organizations focusing on sustainability or energy.

Non-governmental bodies, like the Australian Association of Environmental Educators and Cool Australia, support schools and teachers to implement high-quality environmental and climate change education by providing resources, opportunities for professional development, and sharing of best-practices among educators. Education Services Australia, a national not-for-profit company owned by Australia’s state, territory and federal government education ministers, manages Scootle, an online repository of digital resources aligned to the Australian Curriculum.

Several independent projects support climate change education on a national level. For example, the Einstein Project provides curriculum resources for Years 3 to 10. Students learn about climate change via gamification, using examples of famous scientists.

Cool Australia, a non-governmental organization, also provides teaching resources about climate change. The resources are available for all levels and all subjects, aligned with the Australian Curriculum.

The Primary English Teaching Association Australia has developed many teaching resources, including a Pre-school to Year 8 learning progression on the Language of Climate Change Science, which educators can choose to incorporate in their teaching. This Association further developed Teaching the Language of Climate Science (2021) in consultation with an advisory group of representatives from science teachers’ associations and academics. The Australian Broadcasting Corporation also has a suite of education resources, including some addressing climate change.

Teachers have numerous resources available to support integration of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority of the Australian Curriculum into their teaching, including values of caring for Country. The Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority offers Illustrations of Practice to support educators in embedding this cross-curriculum priority in and across the learning areas of the Australian Curriculum for Years Foundation to 10. Another resource is the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Education Portfolio’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander resources, which include land management, traditional practices, and connection and care for Country. Those resources include aspects of climate change by looking at the health of nature and observing changes in natural cycles.

The 7th National Communication makes no references to teachers or teacher training.

iii. Climate change in higher education

Australia’s tertiary education sector is divided into vocational education/training and higher education, both of which occur at both government and private institutions. According to the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency, Australia has 192 different higher education providers, including 42 Australian universities. This review could not find a higher education sector plan in Australia.

The Report on the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (2018) states that Australia has “an extensive scientific community in government-funded agencies and through the university sector working on a broad range of climate change issues and contributing to the global body of climate research” (p. 85). A number of universities also host dedicated climate change and sustainability organizations or institutes, such as Monash University’s ClimateWorks and the Monash Sustainable Development Institute, Melbourne University’s Melbourne Climate Futures, the Australian National University’s Institute for Climate, Energy, and Disaster Solutions, the Climate Change Research Centre at the University of New South Wales, and Responding to Climate Change at the University of Tasmania.

Almost 90% of Australian universities are members of the Australasian Campuses Towards Sustainability Network, which aims to bring universities together for a sustainable future. The Network organizes roundtables and forums for its members to discuss climate change and to help them become carbon neutral. In particular, the Network helps its member universities participate in international assessments such as the Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System from the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education.

A small number of Australian universities are members of the International Universities Climate Alliance, which seeks to share research on climate change with the public and enhance collaboration between “leading research teams, supporting global leaders, policymakers and industry in planning for and responding to climate change” (n.p.). The Alliance focuses on climate change research, including how to make universities climate friendly.

Many Australian universities have also signed on to the United Nations Principles for Responsible Management Education, which engage business and management schools to provide future leaders with the skills needed to balance economic and sustainability goals by integrating the SDGs into their teaching. This includes the SDGs related to climate action, particularly SDG 13.

Australia’s Long-Term Emissions Reduction Plan also emphasizes the important role of higher education in building the skills of Australians in all regions to address climate change, noting that access to training and learning is important for young people. The Plan highlights the vital role of higher education in research to equip Australia with the necessary technology to reach its long-term emissions goals.

The Australian higher education sector offers high-quality climate change content embedded across multiple disciplinary degrees, plus specialized climate change qualifications at a range of Australian universities. The 7th National Communication (2017) notes 16 universities that offer climate change/sustainability education. These include a bushfire and climate elective at the University of Melbourne, a Master’s of Climate Change at the Australian National University, and a Master’s of Sustainability & Climate Policy at Curtin University.

iv. Climate change in training and adult learning

Australia’s Long-Term Emissions Reduction Plan (2021) emphasizes the importance of skills training for shifting its economy to a lower-emissions design. A key aim of the Plan is to build a skilled workforce: “… developing a workforce with the right skills and expertise is critical in capturing opportunities from low emissions technologies and emerging markets” (p. 89). Creating a clean workforce is one of Australia’s core principles.

In 2019, the Prime Minister and Cabinet Department commissioned an Expert Review of Australia’s Vocational Education and Training System. While the review made no particular observations or recommendations related to creating a climate-skilled workforce, it noted the availability of several certificates and diplomas through the vocational education and training system relating to the environment, sustainability, and renewable technologies. A key recommendation of the Expert Review was the development of a skills commission. The National Skills Commission was established in 2020 to advise on the needs of Australia’s labor market, including strengthening Australia’s vocational education and training system. Several publications from the Commission seek to set out a plan for future skills priorities. The Emerging Occupations report (2020, p. 5) lists sustainability engineering and trades, including solar and wind power technicians, as one of seven groups of emerging occupations (covering a total of 25 emerging occupations), but does not discuss further how this skill requirement can be addressed. The Australian Jobs 2021 report identifies wind turbine technicians as an example of an emerging occupation. However, it does not mention the changing global situation that creates this need or how this occupation will be supported.

Similarly, the Technology Investment Roadmap- First Low Emissions Technology Statement (2020) from the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources emphasizes that “developing a workforce with the right skills and expertise is crucial to capturing the opportunities associated with low emissions technologies and global markets.” (p. 35) The Statement also emphasizes the important role of the National Skills Commission in this process. The Long-Term Emissions Reduction Plan (2021) particularly notes the importance of skills training in the manufacturing, hydrogen, and electricity sectors, such as the US$ 11.58 million (AUD 16.14 million) Energising Tasmania Program partnership between the federal and Tasmanian governments to develop a skilled workforce.

The Learning to Adapt Program developed by the Environment Institute of Australia and New Zealand is a professional development program for established environmental professionals, delivering practical skills and knowledge on climate change adaptation. The Institute also promotes the Certified Environmental Practitioner Program that allows professionals to specialize in several areas, including climate change.

The National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy (2021) notes the importance of training government officials to be climate risk managers. Climate Compass: A Climate Risk Management Framework (2018) brings climate change knowledge to government officials. To reach this goal, government officials have access to data provided on Australia's official climate change website.

A program that builds the climate knowledge and skills of adult Australians is the Climate Reality Project, which empowers members of the public to lead on climate by equipping them with training and tools to educate others about climate and drive change. The local branch of the Climate Reality Project - Australia and the Pacific is hosted by the University of Melbourne. According to their website, “since 2006, more than 2000 people from Australia and the Pacific have been trained as Climate Reality Leaders, helping drive greater public awareness of climate challenges and solutions.” (n.p.)

A number of higher education institutions offer microcredentials—short training programs—in the areas of climate change, environment, and sustainable development. For example the University of Western Australia offers the course Introductory Environmental Science – Ecosystems and Biodiversity.

The Minister for Climate Change and Energy hosted a Climate and Energy Job Summit in 2022. The Summit focused on the clean technologies and renewable energy sectors.

According to the 7th National Communication (2017), the Australian vocational education and training sector builds skills in identifying and managing climate change risks through Registered Training Organisations, which provide training to build skills including “environmental management and sustainability, conservation and land management, environmental technology, sustainable operations, renewable and sustainable energy, energy and water efficiency, and retrofitting buildings” (p. 183).

The 7th National Communication (2017) highlights that the government: 1) provides professional development programs to professionals in the building industry to improve Australia's residential building energy efficiency; 2) supports training workshops for Pacific, Atlantic, Caribbean, and Indian Ocean officials attending the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) meetings and other climate change forums, plus dedicated training for Pacific and Southeast Asian women to enable them to engage effectively in negotiations and build an understanding of the gender dimensions of climate change; and 3) provides capacity development training for Indonesia and Pacific Island nations in forest monitoring, emissions measuring, and reporting.

i. Climate change and public awareness

The National Disaster Risk Reduction Framework (2019) identifies “Improve public awareness of, and engagement on, disaster risks and impacts” (p. 13) as priority action for 2019–2023.

The Australian federal government has run campaigns on climate change awareness, such as the ‘Think Change’ Climate Change Household Action Campaign in 2008–2009. However, this review could not find any federal campaigns since 2008–2009. Some state and territory governments mention the importance of public awareness in their climate action plans, including the Northern Territory (Delivering the Climate Change Response: Towards 2050 – A Three-Year Action Plan for the Northern Territory Government; 2020) and South Australia (South Australian Government Climate Change Action Plan 2021-2025; 2020). The Australian Capital Territory’s Community Engagement Strategy on Climate Change (2014) is more specific, outlining a public awareness campaign called Time to Talk ACT (now completed). The project encouraged citizens to speak out and actively participate in decision making.

Civil society organizations such as the Climate Council, members of the Climate Action Network Australia, the Australian Youth Climate Coalition, and the Seed Indigenous Youth Climate Network have a vital role in raising and maintaining public awareness of climate issues in Australia. One example is the Climate Council’s 12 Climate Actions to Make and Impact campaign. This campaign published 12 examples of what people can do for climate action, such as engaging others in climate change conversations. However, the most widely reported climate action campaign is the SchoolStrike4Climate youth strike movement. It is part of a global movement of young people to demand that their governments take climate change more seriously.

The Monash Climate Change Communication Research Hub researches and implements best practice approaches to communicating climate change, in partnership with leading science and media organizations. Their website lists an extensive series of projects. Climate Communicators is the Hub's flagship program, producing “simple, long-term climate graphics for Australian weather presenters. By detailing city-level climate trends in a simple format, the Program is building an understanding of the local implications of a global phenomenon. And with television remaining the single largest source of news and weather for Australians, it reaches hundreds of thousands of people with each broadcast.” (n.p.)

According to the 7th National Communication (2017), the state and territory governments build public awareness of climate change and associated disaster risks through, for example, action plans, government programs, and public training and networking opportunities. For instance, under the Australian Capital Territory’s Emergency Management Plan (2014), the Territory government builds public awareness of climate disaster risks through community announcements of heatwaves, bushfires, and storms.

ii. Climate change and public access to information

One of the three key objectives of Australia’s National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy (2021) is to “improve climate information and services” as they are “critical to drive action” (p. 28). The Strategy emphasizes the importance of several federal government services, state/territory governments, and private enterprise in providing this access to information. Australia’s Long-Term Emissions Reduction Plan (2021) also includes a focus on “helping consumers with information, knowledge sharing and certification” (p. 9).

The Australian public has access to several online platforms related to climate change, including data on Australia’s emissions and projected emissions via the website of the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. The public also has access to the National Inventory Reports, which the Australian government produces as part of its submissions to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). These inventories report on Australia’s emissions, projected emissions, and how the nation is tracking against emissions reduction targets. The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water supports other Australian government agencies, such as the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO)and the Bureau of Meteorology, to publish publicly available State of the Climate Reports. These reports detail climate trends and climate change projections for Australia.

The Australian government also offers public guidance in making more environmentally friendly choices. For instance, government websites Your Home and energy.gov.au advise the public on how to improve environmental sustainability and energy performance of Australian households, reduce energy bills, and make businesses cost-efficient. The Equipment Energy Efficiency Program provides information on the energy performance of products such as home appliances, and the Green Vehicle Guide outlines the environmental performance of motor vehicles. The Australian government also offers resources for improving businesses’ energy efficiency and climate change adaptations via the Business.gov.au website. Finally, government-supported websites detail climate change impacts on coastal areas. The public can access information on the latest research and local risks of flooding from storm surges and sea-level rise via Coastal Risk Australia.

Other sources of information include the Climate Change Authority, an independent statutory body that develops regularly updated fact sheets on climate science, Australia’s international commitments, and emissions from a range of sectors in Australia. The Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub is a research coalition of government agencies and universities that develops climate webinars, training, publications, and data to inform policy development and the community. The National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy (2021) additionally notes the role of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes and the Australian Antarctic Division in providing up-to-date climate information to the Australian and global communities. The Climate and Health Alliance provides information about the relationship between climate change and health and how the health sector can become greener.

In the 2021-2022 budget (2021), the Australian government committed to developing the Australian Climate Service. The Service is a partnership between the Bureau of Meteorology, Geoscience Australia, the CSIRO, and the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The service supports the National Emergency Management Agency to better plan and prepare for climate and natural hazard risks and respond and recover from disasters when they strike.

Civil society organizations, academics, and numerous other stakeholders are active and contribute to fostering access to and learning about climate change facts and implications. The Climate Change Communication Research Hub at Monash University provides up-to-date resources to, for instance, foster understanding of climate changes impacts. The Climate Change Council is an independent, crowd-funded organization providing quality information on climate change to the Australian public. The Climate Change Communication and Narratives Network seeks to complement existing research activity at Deakin University that is related to climate change, critically focusing on the politics and practices of climate change narration and communication in a time of climate emergency.

iii. Climate change and public participation

Australia’s Long-Term Emissions Reduction Plan (2021) emphasizes the importance of regular reviews of Australia’s climate plans and notes that the federal government will consult widely in its review process “especially with industry and regional communities” (p. 100).

The National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy (2021) mentions the National Indigenous Dialogue on Climate Change (2018), which “enabled Indigenous Peoples from across Australia to come together to provide recommendations about what climate change information, capacity building, and engagement would be of greatest value to Indigenous communities” (p. 25). This Dialogue led to the National First Peoples Gathering on Climate Change in Cairns in 2021, an opportunity to learn from the Indigenous Peoples and share tools and approaches.

Non-governmental organizations such as the Australian Conservation Foundation and World Wildlife Fund advocate for public participation in climate change issues and campaign to influence policy and community behaviors. The Climate Action Network Australia links organizations across Australia to “take actions to protect people at home and abroad from climate change, to safeguard our natural environment, and to build a fair, clean, healthy Australia for everyone.” (n.p.) The Network has over 120 member organizations. The initiatives from those organizations include programs on climate justice and youth engagement and initiatives from and for farmers. Australian Youth for International Climate Engagement brings together young Australians from diverse backgrounds to raise their voices in climate negotiations. Global Voices is another Australian youth-led non-governmental organization that influences policy making and international relations for climate change. Extinction Rebellion Australia organizes citizens’ assemblies, which advocate for more citizen participation in climate change decision making. Groups like Friends of the Earth regularly offer policy submission templates that others can modify and submit.

Non-governmental organizations are not the only non-government stakeholders participating in climate change policy and action. Businesses are involved through groups such as the Australian Industry Greenhouse Network, which works on climate change policy, and the Carbon Market Institute, an independent industry-wide association that aims for businesses to reduce emissions.

According to the 7th National Communication (2017, p. 185), public participation in climate change issues is generally facilitated by the Australian state and territory governments, non-governmental organizations, industry-wide associations, and research institutes. The Communication discusses public participation in tandem with public access to information. It asserts that the government’s information platforms empower the public to take actions in their own lives to reduce their environmental footprint, such as the energy efficiency of their homes and the environmental friendliness of the products that they purchase. The Australian government further states that it empowers the public to take action by providing opportunities for people to participate in state-based initiatives such as the Victoria government’s pledge (developed by Sustainability Victoria) to improve their practices to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

Australia’s Nationally Determined Contributions (2022) highlight that “Domestic institutional arrangements, public participation and engagement with local communities and Indigenous Peoples, in a gender-responsive manner” (p. 17) will be available as appropriate.

i. Country monitoring

The Australian Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Data Reporting Platform notes that reporting on SDG 4.7 (sustainability education) and SDG 13.3 (climate change education) is not applicable because the United Nations has not yet agreed on Indicators. For SDG 4.7, the Australian government does note on the Platform that “concepts of sustainability, social justice and diversity are embedded in the Australian school curriculum.” (n.p.) However, no specific targets or indicators are used to monitor this.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics reports on a number of issues related to climate change, although no data for climate change communication and education were found in this review.

In the Australian government Report on the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (2018), many of the same examples of climate change education found in the 7th National Communication (2017) are mentioned, noting within SDG 4 that sustainable development is part of teaching at many schools and universities. Under SDG 13, the Report states that “the Government provides education, training, research, and information to help Australians understand and respond to climate change” (p. 86). SDG 13 analysis also mentions that the government provides special information for the local and regional levels. No specific monitoring and assessment targets or indicators are mentioned, however.

Australian students participate in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). While these assessments do not specifically measure climate change knowledge, they measure students’ overall awareness of issues such as climate change and students’ science literacy. In the 2018 PISA report, 82.6% of Australian students demonstrated being informed about climate change and global warming, putting them above the OECD average of 78.5%. An Australian Council for Educational Research report notes that in the 2018 PISA assessment, Australian students were ranked 17th of participating countries in scientific literacy. However, Australia’s scientific literacy scores decreased by 24 percentage points between 2006 and 2018.

The Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority also undertakes a regular National Assessment Program. Three sample assessments are administered nationally in Australia: Civics and Citizenship, Science Literacy, and Information and Communication Technology Literacy. Each assessment is administered every 3 years on a rolling basis. The Civics and Citizenship 2019 Report showed that students in both Year 6 and Year 10 named pollution, climate change, and water shortages as their biggest concerns. The percent of students concerned about climate change increased by 9.8% percentage points in Year 10 students and 12.7% in Year 6 students since 2016. The Science Literacy 2018 Report showed that a majority of both Year 6 and Year 10 students believe “science can help us understand global issues that impact on people and the environment” (p. 73).

Public awareness and concern about climate change in Australia can be measured through several independent and non-government surveys and polls. These include the Lowy Institute’s 2021 Climate Poll, which found that 60% of Australians say “global warming is a serious and pressing problem. We should begin taking steps now, even if this involves significant costs.” (a 4-point rise from 2020 and an 8-point rise from 2019). The poll also found that 74% of Australians believe that the benefits of taking further action on climate change would outweigh the costs, and 78% say that Australia should set a target of net zero emissions by 2050. Similar results can be seen in The Australia Institute’s Climate of the Nation 2020 Report: 80% of Australians think we are already experiencing the effects of climate change, 83% support a phase-out of coal-fired power stations, and 71% think Australia should be a world leader in finding solutions to climate change. The 2021 Australia Talks survey conducted by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation found that 68% of Australians think Australia is addressing climate change poorly. The number of people willing to spend over $500 of their own money each year to address climate change has risen by 15% since 2019 to 34% of Australians.

ii. MECCE Project Monitoring

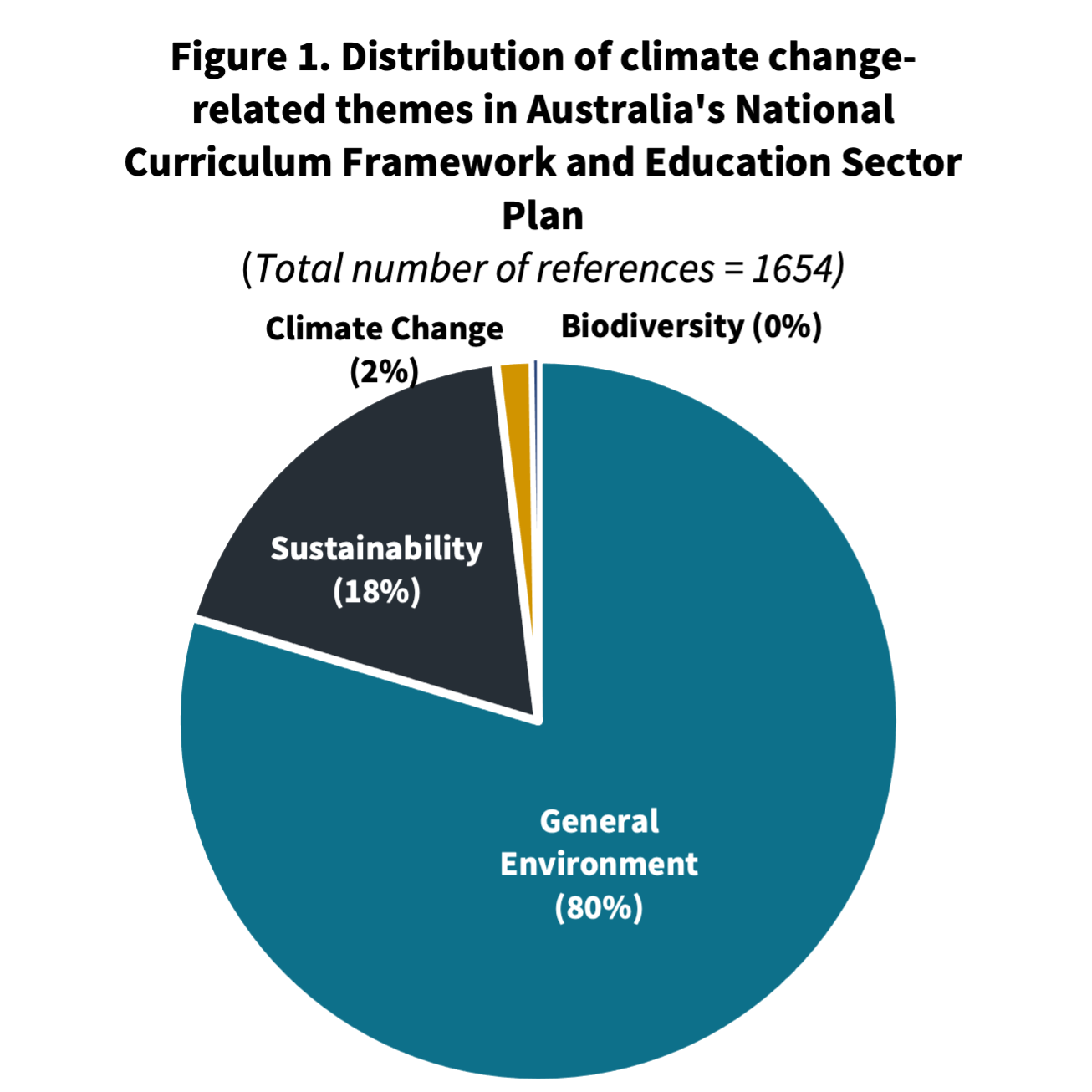

The Monitoring and Evaluating Climate Communication and Education (MECCE) Project examined the F-10 Australian Curriculum (Foundation to Year 10) for references to ‘climate change,’ ‘environment,’ ‘sustainability,’ and ‘biodiversity.’

The Monitoring and Evaluating Climate Communication and Education (MECCE) Project examined the F-10 Australian Curriculum (Foundation to Year 10) for references to ‘climate change,’ ‘environment,’ ‘sustainability,’ and ‘biodiversity.’

Concepts around the ‘environment’ and ‘sustainability’ are mentioned much more frequently than ‘climate change.’ References to ‘climate change’ were found 27 times, references to ‘environment’ 1,317 times, references to ‘sustainability’ 306 times, and references to ‘biodiversity’ 4 times. Figure 1 displays the distribution of references to climate change relative to sustainability and the environment in Australia’s National Curriculum Framework. This section will be updated as the MECCE Project develops.

This profile was reviewed by:

Chanel Bernal and Belinda Emms, STEM Team, Schools Group Department

Amy Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, Professor and Executive Dean, Faculty of Education, Southern Cross University.

Susie Ho, Enterprise Immersion Director, Office of the DVCE, Monash University

Blanche Verlie, Researcher, University of Sydney